The European Sentiment Compass 2022

Summary

- Two major crises – the pandemic and the war in Ukraine – have consolidated support behind the European integration project. But they have also shaken the union’s sense of direction.

- The EU is facing a broad array of challenges, from international security to climate change, to migration, to democratic decline.

- European leaders may be tempted to make trade-offs, such as between the EU’s geopolitical unity and its principled approach to values; between energy sovereignty and the green agenda; between financial solidarity and economic stability.

- But these are more than just problems to address – they also contain the potential to become the centre of the EU’s purpose, which may be redefined in the context of war in Ukraine.

- The free media and a flourishing cultural sector are vital for nurturing European sentiment – and are therefore also essential for Europeans to successfully tackle these challenges and define the EU’s sense of direction in the years to come.

Introduction

Numerous architects of Europe’s post-1945 integration process believed that the success of their political project would require a strong cultural underpinning. Denis de Rougement wrote about the need to awaken a “common sentiment of the European”. Robert Schuman argued that “before being a military alliance or an economic entity, Europe must be a cultural community in the most elevated sense of the term”. And Jean Monnet reportedly said: “If I were to do it again from scratch, I would start with culture.”

Today’s Europe is radically different from the Europe they were contemplating seven decades ago. Still, at least two questions remain as pertinent as ever.

One is whether European cooperation – currently most strongly embodied by the European Union – can work well if the continent’s inhabitants do not also develop a strong sense of belonging. The original approach to European integration was based on principles of legal and political depoliticisation which – according to one astute observer of that process – “enabled the founders to guide any excess of political passion into safer channels”. While the need to create a European public to strengthen integration has long been recognised, success remains limited. With this in mind, one Italian essayist recently remarked that EU institutions’ lack of concerted cultural policies and disavowal of symbolism had led them to adopt “a pragmatic approach entirely devoid of emotion”.

The second question is how to bring into being such a European sentiment. Perhaps a long-term approach is required, deploying political strategies over many decades to generate European sentiment. Such strategies could aim to appeal to shared cultural and historical identity, to the benefits of a functioning political system, or simply to the possibility of being involved in the political process – for instance, by electing European Parliament members or by participating in the Conference on the Future of Europe. Perhaps, however, European sentiment may materialise suddenly, generated in, and by, moments of crisis.

In this respect, Russia’s war on Ukraine could cement the refoundation of Europe that began in 2019. The past months have shown that, after the covid-19 pandemic, Europeans expect more from regional cooperation (and, most importantly, from the EU) than they once did. They may ask themselves why, if it was possible for European leaders to agree a large-scale fund to support their country’s recovery from the pandemic, it is not possible to cease the purchase of Russian energy today.

Europe’s two latest crises have the potential to forge a strong European sentiment. The past two years have shown that citizens retain a steady trust in the EU, which may lead them to conclude it can deliver even more for them. The risk in this is that, the higher people’s expectations, the greater the risk that they could become disillusioned. And they will evaluate the EU’s performance not just on how it responds to the war in Ukraine but also on many other political challenges that Europeans face in the near future. The choices that national and EU leaders make on major issues beyond security and defence will shape Europeans’ views of the EU.

This cannot be a task completed in the political domain, however. To create a European sentiment that stirs, leaders need to ensure there are ways to translate political developments into shared meanings. And to achieve this, the channels of that translation need to be able to operate freely. In this regard, media independence and the freedom of cultural expression in all the EU’s 27 member states are essential. But in some places these are missing – which obstructs the emergence of the European sense of belonging.

To understand European sentiment in early 2022 and how it may evolve in the years to come, the European Council on Foreign Relations and the European Cultural Foundation oversaw a study across the EU. In their respective EU member state, ECFR’s network of 27 associate researchers investigated the relationship between the EU, notions of European integration, and the current political situation. They conducted interviews with relevant policymakers and policy experts and drew on opinion polls and other sources, and in March 2022 they completed a standardised survey. This allows the comparison of the 27 member states on three major issues:

- the effects of the covid-19 pandemic on their country’s attitudes towards Europe;

- the relationship between these attitudes and the following crucial areas of policy: international security, climate and energy, financial solidarity, the rule of law, and migration;

- the situation of cultural actors and the media in their countries – and their capacity to perform the role of translating real-world events into shared political meaning.

This pilot project also seeks to establish how useful the idea of a European sentiment could be in understanding Europeans today – and how they should approach challenges facing the continent.

The war and the pandemic are both novel challenges for the EU. European political leaders therefore require a good working compass to guide them. This paper sets out the various choices that decision-makers across the EU will soon need to make. While they may be tempted to approach some of them as trade-offs – such as between the bloc’s geopolitical unity and its principled approach to values, between energy sovereignty and green agenda, between financial solidarity and economic stability – they should instead look for ways to reconcile the apparent dilemmas. They should also recognise the importance of independent media, vibrant cultural sectors, and freedom of expression in these endeavours. At stake is not just the meaning of Europe in the eyes of its citizens – but also the acknowledgment of the EU as the edifice that can uphold security, prosperity, and freedom in the decades to come.

Consolidation in the pandemic

In December 2020, as the second wave of the pandemic continued to spread, ECFR observed that there was still huge uncertainty as to whether the crisis would strengthen unity among member states, or weaken it. Although the pandemic is not over, it is now possible to address this question.

Covid-19 has proven to be a largely consolidating experience for people’s attitudes to the EU in most member states. According to insights from ECFR’s 27 associate researchers, in no member state has the pandemic been mostly an alienating experience in terms of how much citizens identify with Europe and how European they feel. In more than half of the countries, it has mostly been a mixed experience: alienating and consolidating at the same time.

This is understandable, given the ups and downs in the EU’s reaction to the pandemic. European solidarity did not come quickly or easily; the start of the pandemic will be remembered for the closure of borders, export controls on medical products, and the déjà vu of sensitive debates about money. The early challenges the EU faced in procuring vaccines at sufficient scale and speed bruised its image in the eyes of citizens.

On the more positive side, member states reached a historic deal on the NextGenerationEU fund for those member states most affected by the pandemic, paving the way for some mutualisation of debt in the bloc. The EU has also coordinated the purchase of covid-19 vaccines, which ended the competition among member states for privileged access. And it has succeeded in rolling out the European covid-19 passport, which is spurring the recovery of pan-European travel.

The researchers’ aim with this question was to identify the dominant mood in their respective member states concerning attitudes towards Europe. In eight countries – Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Denmark, Latvia, Portugal, Romania, and Slovenia – the researchers reported that covid-19 has even proved to be mostly a consolidating experience. Meanwhile, in five other countries – Belgium, Hungary, Ireland, Lithuania, and Spain – people seem to have lived covid-19 as mostly a national story – one that has little wider European meaning.

The EU therefore appears to have performed well in the pandemic both in terms of actions and perceptions. Public trust in the EU has largely returned to levels seen before the pandemic. According to the latest Eurobarometer, 47 per cent of EU citizens declared that they trusted the EU in early 2022, compared to 46 per cent in late 2019. It perhaps matters that the union made its biggest mistakes early on but ended on a much stronger note, rather than the other way round. In Italy and Malta, perceptions of the EU hit a low point in mid-2020 (leading many Italians to say they wanted to leave the eurozone and the EU) but have more than recovered since then. However, in only 11 countries has trust in the EU improved in that period. In 15 it has declined, although in just two countries – Greece and France – does distrust towards the EU clearly dominate among the population. In 14 member states at least 50 per cent say that they trust the EU.

It is much harder to identify whether public expectations of European cooperation have also stayed the same. But there is other evidence suggesting expectations have risen. Today, there are frequent calls for the EU to stand up to Russia – even though security, defence, and foreign policy are not part of its exclusive competencies. ECFR polling shows that Europeans see EU cooperation as necessary, and national action as insufficient, in preparing for the next pandemic and providing border security. In late January 2022, Europeans also generally wanted both NATO and the EU to come to Ukraine’s defence in the event of a Russian invasion. All in all, while trust in the EU might have changed little compared to before the pandemic, expectations vis-à-vis the union seem to be growing, suggesting citizens’ European sentiment has strengthened.

At the political level, member state governments now appear to be more positive towards the EU too. According to ECFR’s research, no EU government has become more negative towards the European project in the past two years – while almost half have grown more positive about it. Usually this happened either because governments changed (as was the case in Bulgaria, Germany, Estonia, Italy, Slovakia – and most recently Slovenia), or because an internal balance within the government has shifted in favour of a more pro-European stance (as happened in the Netherlands). Covid-19 was not always the main cause behind the rise in these favourable attitudes. Presiding over the EU Council amid the pandemic might have helped the governments of Portugal and Slovenia to appreciate European cooperation more – although solid examples of European solidarity such as the NextGenerationEU recovery fund and the vaccine roll-out will also have played a role.

As a result, the EU is currently dominated by countries whose governments hold positive attitudes towards it – including the major economies of Germany, France, Italy, Spain, and the Netherlands. The German and the Dutch prime ministers talk of European sovereignty and strategic autonomy – issues that, five years ago, only seemed to matter to the newly elected French president. Only two countries – Hungary and Poland – are currently ruled by governments that persist in holding a negative attitude to Europe. In Poland’s case this might improve as a consequence of the war in Ukraine.

All in all, the EU as a political union seems to have consolidated during the pandemic. While it made mistakes, the union showed itself capable of ensuring its members cooperate to allow bold decisions –which could hardly have been taken for granted before the crisis began.

The map of European sentiment

Europeans began 2022 with a shared experience of trauma and slow exit from pandemic restrictions. This may prove crucial in how they handle the coming strategic challenges facing Europe.

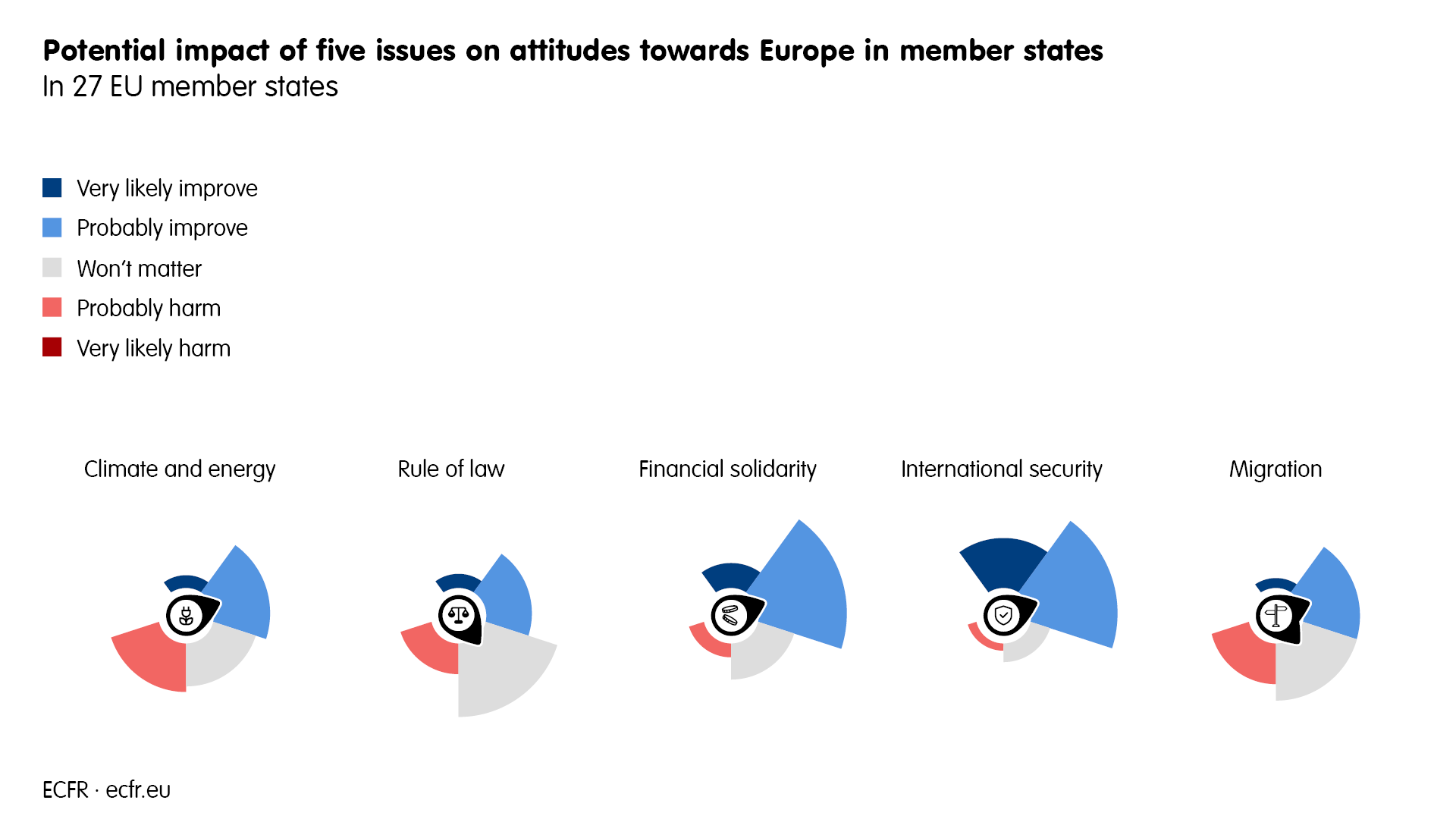

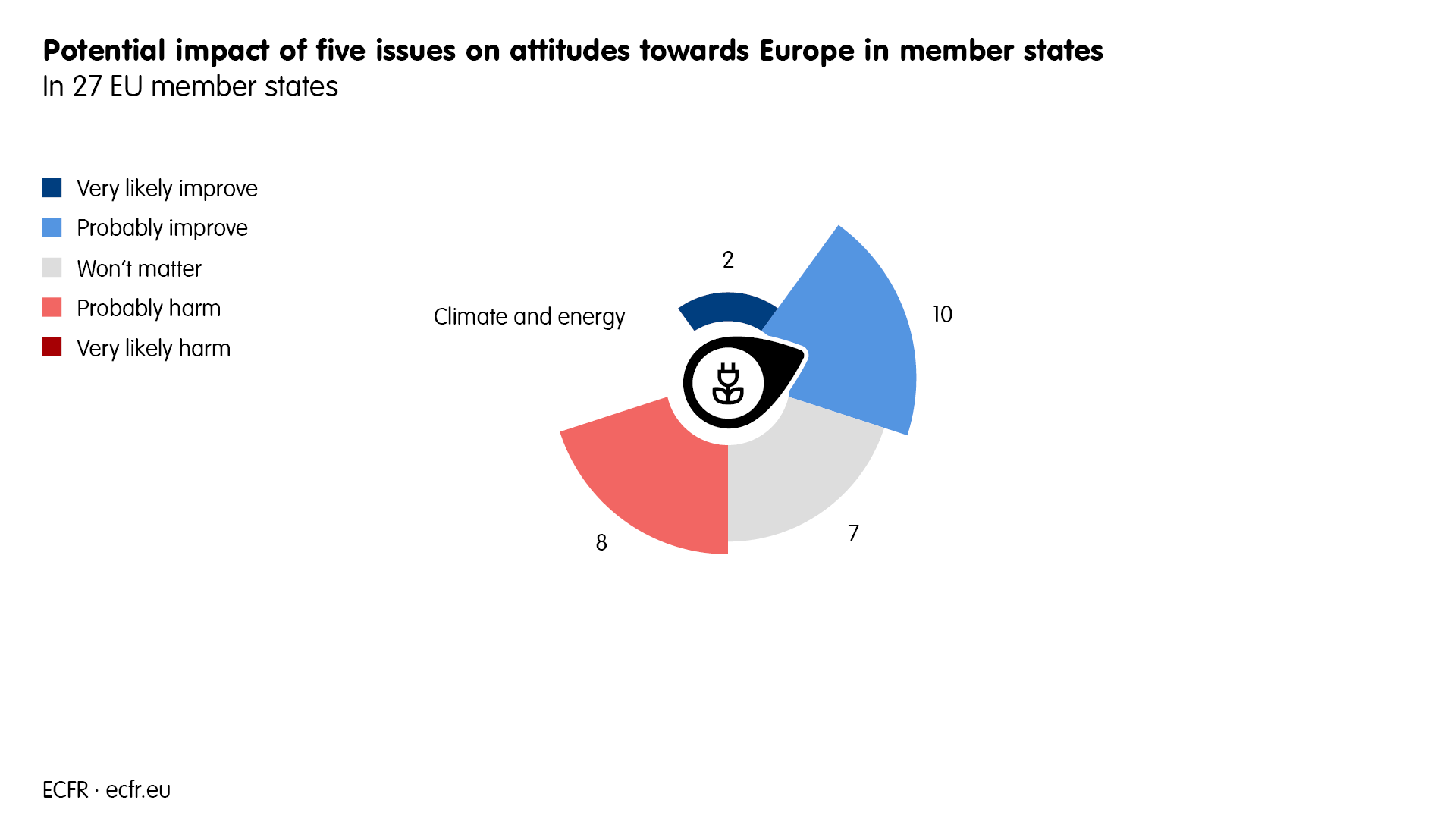

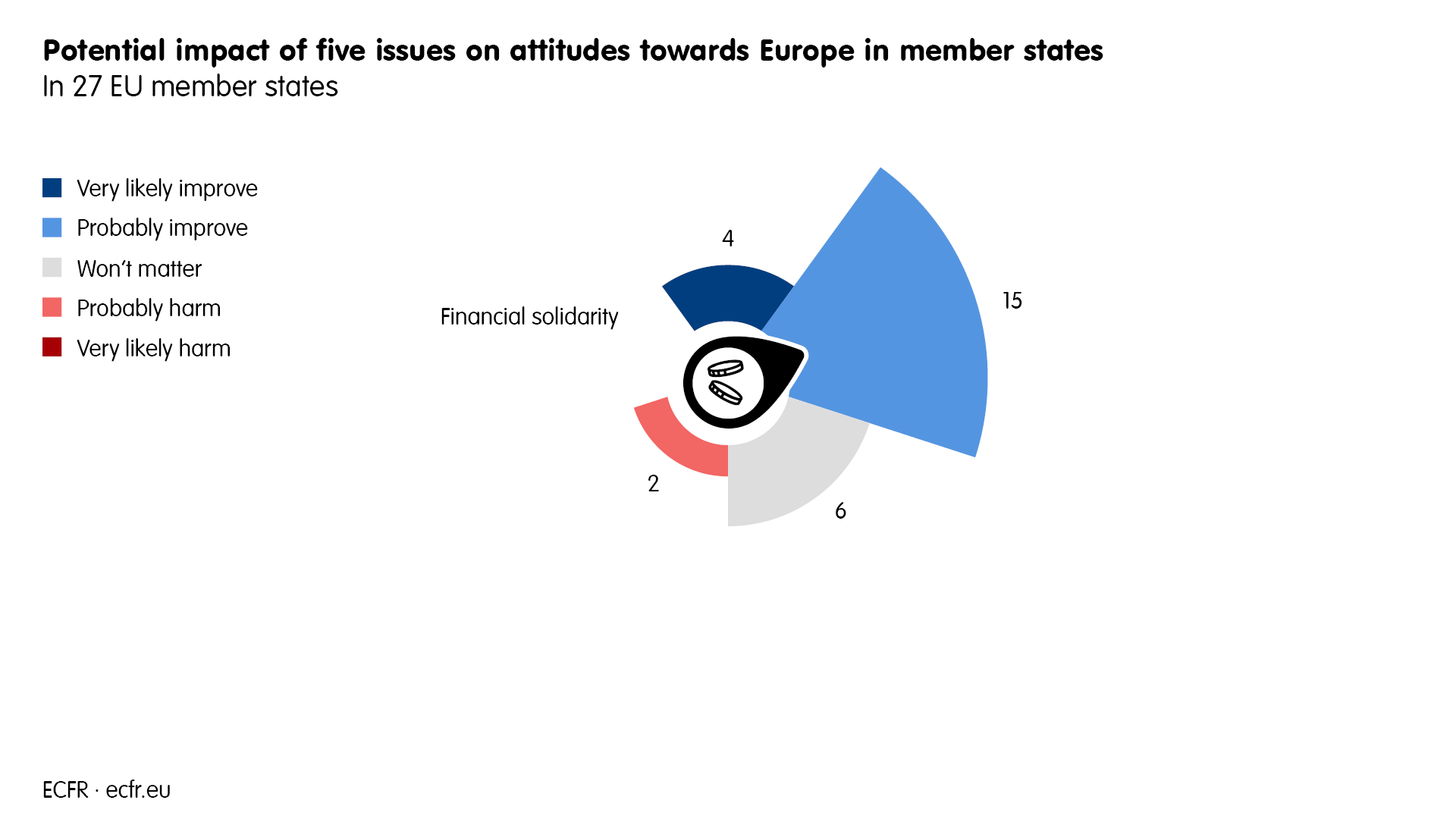

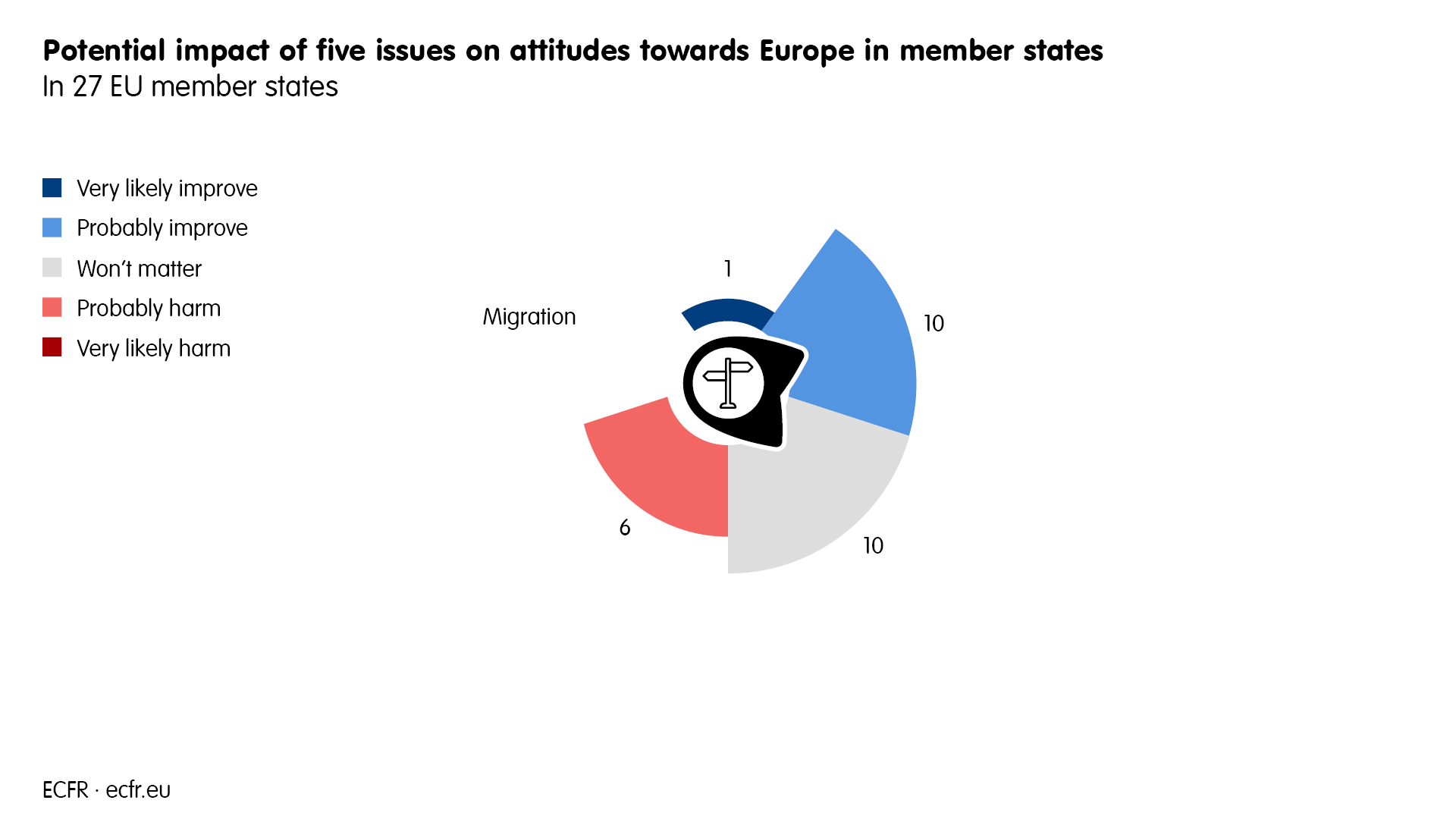

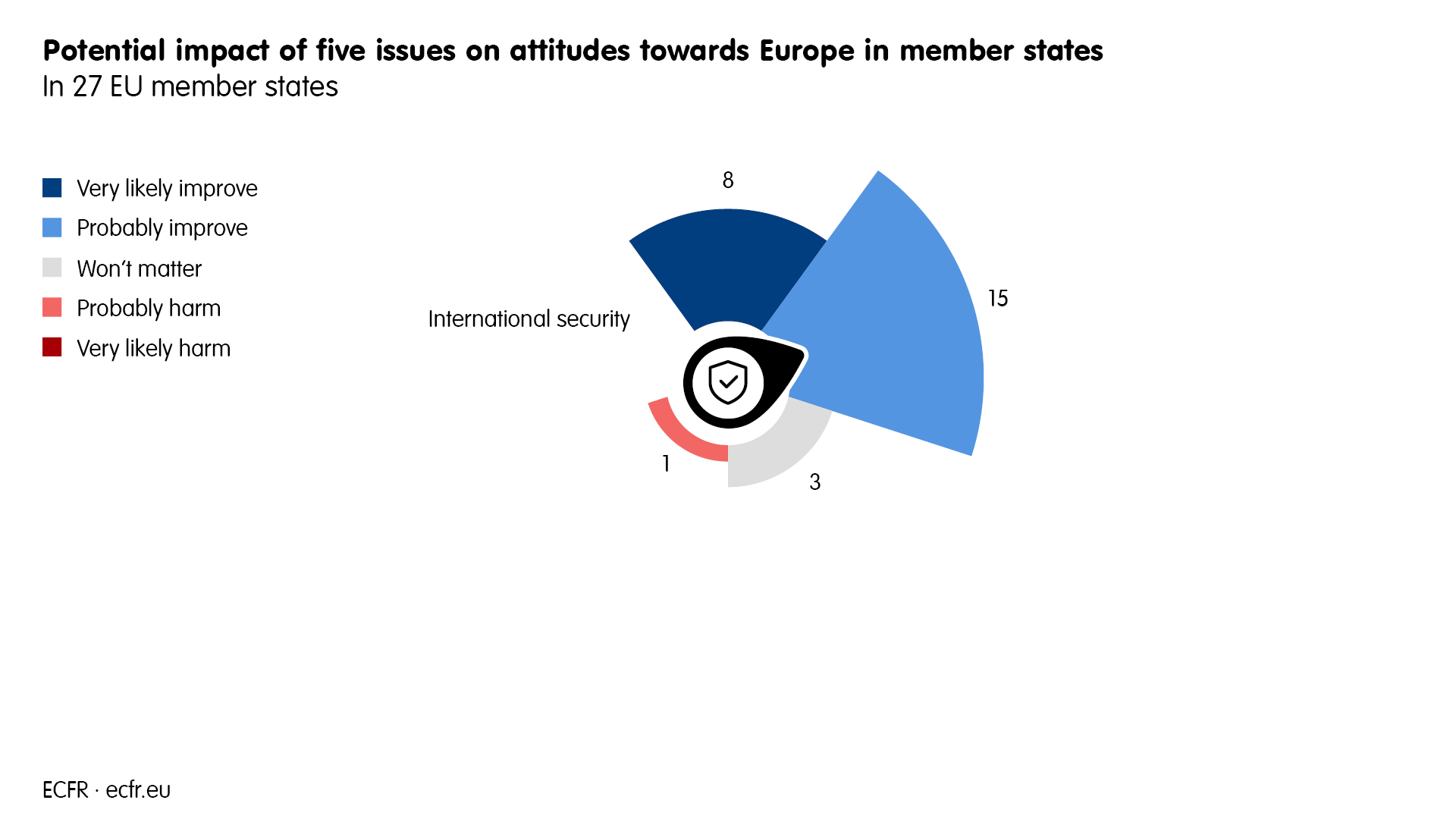

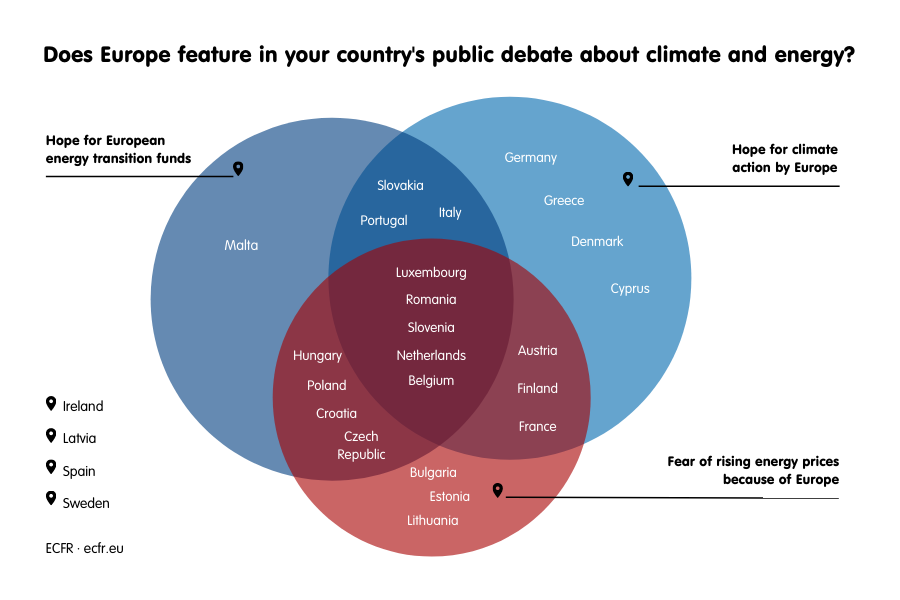

There are at least five such challenges, the most immediate of which concerns international security. But just as important are the decisions that Europeans will need to take on climate and energy, financial solidarity, the rule of law, and migration. EU success in addressing these would improve attitudes to Europe; failure would worsen them.

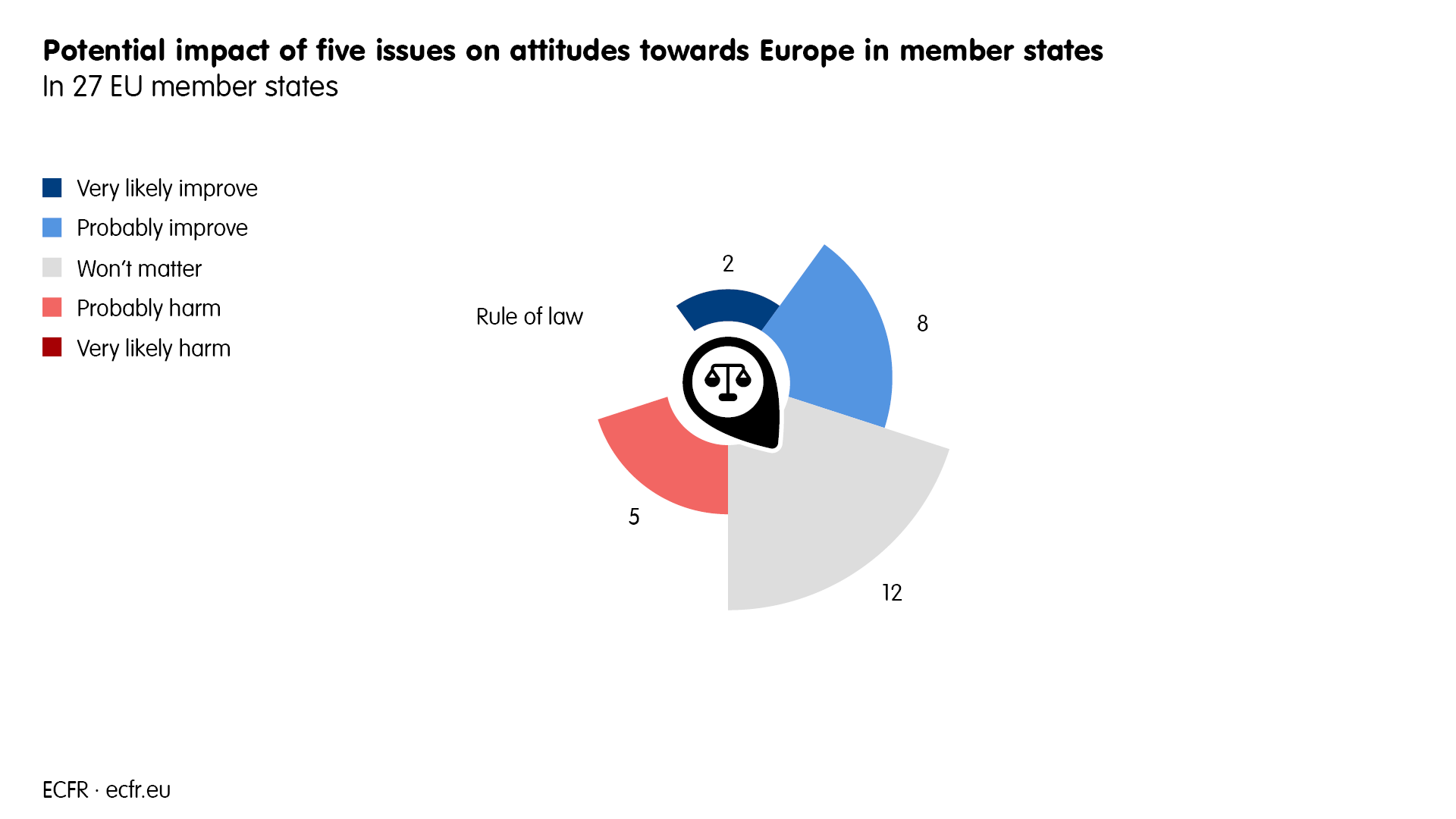

ECFR’s research across the member states reveals that issues related to international security are likely to have the greatest positive influence on overall attitudes. This is closely followed by financial solidarity – although expectations seem to be more cautious on that front. Climate and energy is potentially the greatest risk area, while the rule of law and migration seem to have the least impact on attitudes either way – although, for those countries where they are a priority, they can prove quite divisive. Finally, all these issues, on balance, appear to hold the potential to improve attitudes towards Europe rather than be likely to harm them.

What follows is a more detailed look at each of these areas across the EU27.

International security

“If you want to be a soft power, you need hard power first”, said the EU’s high representative for foreign and security policy, Josep Borrell, commenting on what war in Ukraine means for the EU.

This is more than just a paraphrase of the Latin proverb, Si vis pacem, para bellum. The war has reminded Europeans that they need military capabilities, alliances, and other tools not just to preserve peace in Europe, but to allow the development of strong economic and cultural relations – which in turn also help preserve peace. This model has worked perfectly within the EU – but it has failed vis-à-vis Russia. If Europe needed a justification to become a strong geopolitical actor, Russia’s aggression against Ukraine has provided it.

ECFR’s research suggests that strong EU action on the current urgent security threat will improve its image across EU member states. In particular, in eight countries – both the big ones, such Germany and Italy, and the smaller ones, such as Cyprus and Estonia – an improvement in attitudes to Europe is seen as very likely.

The dynamic is particularly interesting in the six EU members – Austria, Cyprus, Finland, Ireland, Malta, and Sweden – that are not part of NATO. In Sweden and Finland the war has led to intense discussions about possible NATO membership, with some polls showing that the majority of their populations would be in favour. Meanwhile, in Cyprus, recent events have reminded citizens of the protection the EU affords them from the assertiveness of global players. In Austria, the war has generated some discussion about the country giving up its neutrality and joining NATO, although this remains unlikely: a clear majority of Austrians prefer to remain neutral. In the two other “strategic schnorrers”, Ireland and Malta, the issue of neutrality is also sensitive – although, in the month after the invasion, one poll in Ireland showed that support for joining NATO among the population had increased drastically, from 34 per cent in January to 48 per cent in March. Equally, Ireland’s leaders are now calling for an “informed and respectful” debate on neutrality, and are re-examining the funding of the country’s armed forces in the new geopolitical context.

In Denmark, defence and security issues may sharpen national attitudes that have long held great salience with regard to national debates about European integration. In response to the war in Ukraine, the country has decided to hold another referendum on whether to maintain its long-cherished opt-out from the EU’s common defence and security policy. This could at last convert Denmark into a whole-hearted member of the bloc, rather than one interested mostly in economic aspects of cooperation. However, in the coming months this debate risks further polarising Danes in their attitudes to Europe.

The war may not affect attitudes towards Europe as strongly among the EU members located further from the conflict zone – as is the case of France, Spain, and Ireland. But it could be crucial for how the EU’s eastern members perceive the union. In Poland, the geopolitical storm seems to have made some circles within the ruling Law and Justice party more open to softening its approach to, and thereby rebuilding its relationship with, the EU.

Among some of the later-joining EU members, war in Ukraine provides an opportunity to reconfirm their European commitments. Bulgarian prime minister, Kiril Petkov took care to declare: “We are not in NATO, we are NATO. We are not in the EU, we are the EU.” Despite historically very close relations with Russia, a clear majority of Bulgarians supported harsh European sanctions against Russia.

But ECFR’s research also suggests that Poland and other EU member states nearest to Russia and Ukraine (such as Lithuania, Estonia, and Romania) also tend to demand the most from the EU in response to the conflict. Their governments are among the strongest supporters of Ukraine’s EU membership bid. They are often wary of French president Emmanuel Macron’s regular telephone calls with his Russian counterpart, Vladimir Putin; or of Germany’s reluctance to hit Russia with the EU’s energy embargo. They fear that the EU could betray Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky by failing to provide him with sufficient support, pushing him to accept a damaging peace agreement, or moving too quickly towards a de-escalation with Russia. If that were to happen, it could reinforce the perception of a deep east-west divide within the bloc.

Climate and energy policy

War on the EU’s border has for the moment overshadowed the issue of climate change, which the EU had sought to make a priority. However, given Europe’s dependence on Russian fossil fuels, the security situation makes it all the more necessary for member states to diversify their sources of energy. And last month’s third IPCC report underlines the extent to which the window for keeping global warming at 1.5 degrees has all but closed.

There appear to be major differences on whether this issue is likely to improve or harm attitudes towards Europe within different countries – but the variations partly reflect differing expectations around how the EU is planning to resolve its apparent climate versus security dilemma. ECFR’s research suggests some Europeans fear that reducing the bloc’s dependence on Russia might require delays to decarbonising the economy, a short-term increase in the use of coal, and investment in the nuclear sector. But others believe this is exactly the moment for Europe to finally put its money where its mouth is – by betting on the green transition and divesting from Russian fossil fuels.

This debate is highly controversial, particularly because energy prices are already high and could rise further as a consequence of disrupted gas, coal, and oil trade with Russia. While Europeans are discussing whether to impose an embargo, Russia has already announced the halting of gas deliveries to Poland and Bulgaria.

The risk of higher energy prices is one of the reasons why, before the war, opposition to the EU’s climate policy was emerging as a favoured topic for far-right parties in several member states. In Poland, the government launched a huge billboard campaign in January 2022, accusing the EU of forcing a rise in energy prices because of its exaggerated green agenda ambitions. In the Czech Republic, politicians notorious for instrumentalising the debates about migration or vaccines (such as Tomio Okamura and Vaclav Klaus) were increasingly engaging in questioning the climate agenda. This picture is by no means uniform, and can be influenced by geography. For example, in Finland, the war in Ukraine has led some prominent members of the far-right Finns Party to support cutting Europe’s dependency on Russian fossil fuels by pushing forward with the green transition.

Still, the risk that climate discussions will sour public attitudes towards Europe and assist anti-European forces is particularly apparent in eastern EU member states – where there is a relatively high dependence on Russian energy imports and where electricity constitutes a relatively large share of domestic living costs. The Polish government has already suggested that, given the war in Ukraine, the EU’s green deal ambitions should be tempered. In Hungary, the prime minister, Viktor Orban, has in recent months claimed that it is thanks to his good relations with Russia that domestic energy prices are still low – and that it is partly due to the failure of Brussels that they have increased elsewhere in Europe. Therefore, in some places the sense could emerge that Brussels and wealthier EU members are imposing costly climate policy on poorer countries, especially in central and eastern Europe, where countries risk being hardest hit by the consequences of the transition.

The EU will need to tread very carefully on these issues. However, it should not give up on its climate ambitions, not just for the sake of climate but also because many Europeans expect it to act. In countries where there is little public trust in the national government, Europe is often seen as the only actor capable of engaging in the green transition. For example, in Italy – an EU member with one of the highest numbers of violations of the bloc’s environmental laws – many citizens would need to look to the EU to hold their own country accountable. But in other larger and wealthier countries too – such as Denmark, Finland, Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden – ECFR’s research suggests that citizens view the EU as a crucial framework for the mainstreaming of climate action.

As a result, in all but seven EU members (Ireland, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Bulgaria, Spain, and Sweden), Europe features in national debates about climate and energy as a source of hope – whether it is a hope for climate action by Europe, or for European energy transition funds, or both. Only in Bulgaria, Estonia, and Lithuania does it mostly feature as the source of blame for rising energy prices. And, in 12 countries, hope and fear vis-à-vis the EU’s climate action are intertwined.

This points to the communication side of the challenge. Far-right parties across the continent might benefit from the green transition by promoting a narrative of European elites forcing sacrifice on citizens and reducing their living standards and liberty. In Spain, the Vox party is already testing out this framing; it was also visible during the gilets jaunes protests in France. However, it is also possible to imagine another, more convincing, story. To start with, living standards are not just about how much money people have in their wallets, but also about whether the place they live in is free of pollution. And it could also be possible to counter far-right mobilisation strategies by showing that Europe is capable of standing up to the urgency of climate change, that the EU has the tools to help member states navigate this difficult transition, and that the green transition is another way in which Europe can contribute to international peace.

Financial solidarity

The costs of the EU’s strategic decisions – such as those to reduce energy dependence on Russia, to punish the Putin regime with economic sanctions, or to host Ukrainian refugees – are spread unevenly across member states. As noted, in several countries populists are likely to try to use the green transition and rising energy prices to consolidate their political position at home. But while the NextGenerationEU funds are already meant to support the green transition in Europe, more might be needed to help citizens through the current shock provoked by war in Ukraine – not least because of Russia’s decision to halt gas exports to some EU countries, and to make it possible for Europe to reduce imports of Russian energy.

For example, Bulgaria might need such support not just because of its strong dependence on Russian energy and metals, but also because tourism contributes significantly to its GDP, with a big role normally played by Russian and Ukrainian visitors. Cyprus is nervous too. In the past, it has been notorious for courting Russian businessman who hold their money in the country’s banks, purchase luxury real estate on the island, and contribute to the country’s revenues as tourists. But, as a result, it will be hit more than most by the EU’s sanctions on Russia. Without some support, and feeling left alone, the Cypriot government could decline to back future EU sanctions or other foreign policy decisions that require unanimity.

Meanwhile, countries such as Poland, Romania, and Slovakia might need support to cover the cost of looking after Ukrainian refugees – which is non-negligeable for their public finances.

Paradoxically, covid-19 has made extending financial solidarity both more and less possible. The pandemic has shown that member states are ready to stand up for each other in the most difficult of times. They have broken the taboo of issuing joint debt on a massive scale – something that was unthinkable a decade earlier during the eurozone crisis. Yet covid-19 has also stretched public finances to their limits in many countries, including the EU’s wealthiest member states. This might discourage them from agreeing to another emergency fund.

This idea is already generating criticism in Finland, a country that belonged to the “Frugal five” grouping two years ago (alongside the Netherlands, Sweden, Denmark, and Austria). The Finnish prime minister, Sanna Marin, has already dismissed the idea of funding the EU’s future energy and defence projects by raising common debt. Similar reticence can be expected in Denmark, Sweden, the Netherlands, and Germany.

The EU could help ease some of the tensions if it agreed new sources of revenue to help pay for the new deal. Some solutions could even be integrated into how the EU reduces its energy dependence on Russia: for example, if it introduced an import tariff on Russian fossil fuels, this could both help support Ukraine and go towards covering the costs of care for Ukrainian refugees.

The nature of the crisis should allow Europeans to make a convincing case for an additional round of solidarity. Member states were able to agree joint debt in 2020 but not a decade earlier partly because it was no longer possible to make moral arguments about countries being guilty of their own financial problems (even though some political leaders, like Dutch finance minister, tried that card). The same can be said of today’s situation. The EU’s eastern members cannot be made responsible for their geographical location, which largely explains why some of them rely more on energy imports from Russia, and why they are the main hosts of Ukrainian refugees.

Rule of law

The most powerful way to convince sceptics to support greater financial solidarity for struggling member states is to ensure that these funds are spent in a transparent and efficient way. The rule of law is vital to this.

Worryingly, this seems to be an issue of secondary importance in most EU member states in the current context – as reflected by the fact that research in 12 countries suggests that the issue is unlikely to move opinion on Europe in either a positive or a negative direction. However, it does appear to matter in Poland, Slovenia, and Romania, which are among the few countries that have faced particular scrutiny on the issue in recent years (although, surprisingly, ECFR’s research suggests that it is not expected to affect attitudes towards Europe in the remaining two: Hungary and the Czech Republic). It also matters to the main net payers, such as Germany and the Frugal Five, which are most concerned about how the money that they contribute is being spent by others.

The rule of law is also an area in which the EU’s direction of travel is currently most uncertain. This could explain why in countries such as the Netherlands and Austria, on the one hand, and Finland and Germany, on the other hand, opinion seems to differ so much in whether this issue could improve or harm domestic attitudes towards Europe. The former appear to be more positive – and the latter more sceptical – about the EU’s capacity to protect the rule of law and fight corruption in member states.

Poland is at the centre of this tension between a geopolitical Europe and a union of values. As discussed, the war in Ukraine has created openings for a compromise between Warsaw and Brussels – although it remains unclear which side would need to make the greater concessions to achieve this. Some European leaders seem to be sympathetic to the Polish government’s argument that geopolitics should currently take precedence over disagreements about the rule of law. Poland’s leading role in supporting Ukraine and hosting Ukrainian refugees has surely strengthened its European credentials.

Polish public opinion is supportive too, although it is also inconsistent. According to a recent poll, 66 per cent say they want the Polish government to end tensions with Brussels and accept its recommendations concerning the rule of law. But, in the same survey, 55 per cent agree that, in the face of the war in Ukraine, and the challenges Poland is facing, the EU should stop demanding that Poland respect the rule of law, and that it should release NextGenerationEU money unconditionally.

In a way, whatever the solution, the rule of law is likely to inflame Poles’ attitudes to the EU. Too soft a position from the European Commission would demoralise opposition supporters; too hard a line could further radicalise Law and Justice voters. More importantly, however, the shape of any compromise will likely affect public attitudes towards the EU in other member states too, and in neighbouring states. If Brussels concedes too much, more Europeans could grow reluctant to consider further enlargement of the union – exactly at the time when Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia have announced their accession ambitions.

Even before the war, this was a toxic and divisive debate for the EU. In some countries – including Cyprus, Bulgaria, Romania, and Croatia – the rule of law is considered by the public as one of the areas in which the EU can make a useful difference, as confirmed by European Parliament polling. For example, in Croatia, the media praised the work of the European Anti-Fraud Office in relation to cases of misuse of European funds in the country. Similarly, in Romania, support is strong for the EU’s rule of law conditionality – assisted no doubt by the fact that a Romanian, Laura Codruta Kovesi, currently serves as the European chief prosecutor. She formerly led Romania’s National Anti-Corruption Department, which exposed cases of high-level corruption in the country.

However, in other places – notably Estonia, Greece, Poland, Hungary, Italy, Malta, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, and France – part of the discussion on rule of law is about the EU going beyond its core competencies in dealing with the rule of law and impinging on the national sovereignty of member states. Most problematically, those questioning the EU’s rule of law activism might have a point – as recognised by even some scholars who are otherwise sympathetic to the cause but who admit that the rule of law is an essentially contested concept.

Currently, Poland and Hungary are the two EU members whose recovery and resilience funds have not been disbursed because of rule of law concerns. These funds (including grants and loans) amounted to 7 per cent and 5 per cent of the GDP of these countries’ respectively in 2020. It may be tempting to conclude that Hungary is already a lost cause. Orban recently won a fourth consecutive term and he may set about blackmailing Brussels on this issue, presenting the European Commission’s decision to withhold these funds as a fundamental injustice. But, if Brussels mends its relationship with Warsaw, this could weaken Orban’s hand, notably since his closeness to Putin has put the Law and Justice-Fidesz political alliance under strain. In early April, Ursula von der Leyen said that the European Commission would use a new conditionality mechanism against Hungary, which would allow Brussels to hold back even regular EU funds from it for not abiding by European norms.

So perhaps within this overall picture there is an opportunity for choosing both geopolitics and rule of law, rather than sacrificing the latter for the former. One could even make the case that a geopolitical Europe and a union of values cannot exist one without the other. If Russia is trying to remake the European order and prevent the EU from applying its values and standards internationally, now is not the time to lower the bar.

Migration

Migration – which divided Europe so severely seven years ago – remains an issue that political leaders should not put to one side.

ECFR’s public opinion poll conducted in 12 EU countries just before the invasion of Ukraine revealed that Europeans feared that coronavirus and climate change were the biggest threats facing Europe today. Migration came third, on a par with the economic crisis. Most importantly, however, in only two countries (Hungary and France) did migration come out on top; in just two others it came either second (Greece) or third (Estonia). Only 19 per cent in Italy considered migration to be one of Europe’s top two threats. Russia did not feature heavily in Europeans’ fears at that time: in only four countries – Estonia, Poland, Sweden, and Denmark – did the country dominate as the main threat.

Among other things, this shows the effectiveness of Orban’s propaganda machine in Hungary. But it would be premature to conclude that migration will not come to dominate the public debate in some member states once again. This could certainly happen if there was a large increase in the number of Middle Eastern and African migrants crossing to Italy, Greece, or Malta.

But, until that occurs, all eyes will be on Poland, Romania, Hungary, and Slovakia as the frontline hosts of Ukrainian refugees. So far, over 5 million Ukrainians have fled the war to other countries, over 50 per cent of them to Poland. Most importantly, EU governments and citizens have demonstrated admirable levels of solidarity with these refugees.

This poses at least three important questions. One concerns the possibility of using the current moment to engage in the long-delayed reform of the EU’s asylum system. This is a point that some countries such as France, Spain, and Italy have been advocating for some time. In the past, central and eastern European countries were among the fiercest opponents of such a reform. Now they have the biggest interest in seeing European solidarity in action – either in the form of relocation schemes or financial support for hosting refugees.

The second question pertains to the risk of a sharp rise in anti-migrant sentiment in Poland and other member states hosting large numbers of Ukrainian refugees. For the moment, there is little sign of this, as people are mostly in solidarity mode. But the Polish far-right has already started playing on anti-migrant fears, including through disinformation campaigns on internet. They are likely betting on a rise in xenophobia once the initial wave of sympathy towards Ukrainian refugees subsides, and as the economic crisis pushes people to start considering them rivals for access to jobs, public services, and dwindling fiscal resources. This may explain why Poland is among the six countries of the EU (alongside France, Italy, Malta, Slovenia, and Finland) where the issues related to migration are expected to harm the country’s attitudes towards Europe, according to ECFR’s research. Political leaders should seriously prepare for the emergence of such a scenario – and consider how burden sharing and financial solidarity could address this.

The third question concerns the warm reception of Ukrainian refugees – which stands in stark contrast to that of Syrian refugees in 2015 – and whether it reveals an uncomfortable truth about Europe. More explicitly: does it expose an ethnocentric angle of the European project?

Arguably, countries such as Poland, Hungary, and Slovakia are much more welcoming to Ukrainian refugees than they were previously towards migrants coming from more distant regions, cultures, and religions. Poland hosts almost three million Ukrainian refugees while continuing to push back non-European refugees at the border with Belarus. These double standards can at least in part be explained by the cultural and – in the case of Poland or Slovakia – linguistic proximity to Ukraine. As for Hungary, many of the refugees crossing the border from Ukraine come from the Hungarian diaspora.

But it also appears that welcoming Ukrainian refugees would not provoke major controversies elsewhere in Europe. During the presidential campaign in France, Eric Zemmour paid the price for his dogmatic opposition to accepting refugees; Marine Le Pen, his main rival on the far-right, outperformed him in the race, after showing more solidarity towards Ukrainians escaping their homes – even if this struck false chord with her previous position on Syrian immigration, and the enduring anti-migrant theme in her political programme.

To some extent, 2015 and 2022 are hardly to be compared. Europeans are currently being forced to react to a war on their own continent rather than a conflict in the wider neighbourhood. At the same time, however, it is hard to avoid the impression that – with this war, the arrival of Ukrainian refugees, and the EU membership bids by Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia – the limits of European culture are becoming exposed. Mainstream politicians have traditionally treated such issues as an identarian taboo – but they may be forced to deal with them before too long.

The emergence of European sentiment

European sentiment does not come into being through government legislation, nor does it emerge spontaneously among citizens. Numerous other, intermediary, actors are involved. They help interpret events, converting them into narratives and shared understandings. They also create new values and meanings. Importantly, such actors increasingly operate in the European public sphere, rather than being limited to the borders of national debates. However, they still function within frameworks largely set by both European and national policies.

Many types of group play a role in this process. But this paper concentrates on two specific actors – the cultural sector and the media – whose role in shaping European sentiment is crucial but often insufficiently acknowledged or misunderstood. The main question is whether these groups can usefully serve that purpose today in each EU member state – and what it would take to make sure they can.

Cultural sector

The foreign policy sphere often struggles to recognise the role played by the cultural sector in bringing Europeans together and generating shared meaning about Europe. Instead, politicians, policymakers, and policy experts typically tend to overestimate the impact of their own work.

In comparison, across Europe there is a busy agenda of music, theatre, cinema and other cultural festivals; the continent’s landmark cities that become a European Capital of Culture for a year; books that prompt debate about history or laugh at Brussels politics; and – last but not least – the annual commotion of the Eurovision Song Contest. Culture plays a leading role in generating a sense of Europeanness. It has also been the silent hero during the latest two crises, bringing people together and keeping their spirits up in difficult times.

To some extent, European policies can help culture perform that role. True, it took several decades for the first cultural chapter to appear in the EU Treaties – but since 1992 the EU has more sound policies and tools than ever for fostering cultural cooperation and exchange. The Erasmus programme has probably been one of the most successful drivers of European sentiment since the EU’s inception. In 2018, the EU’s New European Agenda for Culture set three strategic priorities for culture at the European level, focusing on the social, economic, and external dimensions. The realisation that culture is closely related to today’s key challenges for Europe (including on foreign policy), and therefore needs to be part of response, is slowly on the rise.

At the same time, however, cultural policies still tend to be treated as “the poor cousin” of the EU’s other policies. Italian essayist Giuliano da Empoli argues that this leaves the field clear for nationalists to tell inspiring stories instead. He argues for a “cultural recovery plan for Europe” through which artists take on the challenge of making European integration less dull, less technocratic, and more passionate.

While this would no doubt be a helpful development, cultural policies are still implemented mostly at the national level. To understand whether the sector has sufficient resources and the necessary freedom to perform such a role, attention therefore needs to focus on what is going on within the member states.

Since the start of the pandemic, culture has faced serious difficulties across Europe. One study put the sector’s drop in total revenues at 31 per cent between 2019 and 2020. This made it one of Europe’s most affected sectors, on a par with air transport and ahead of tourism. The authors of the same report point to the cultural sector’s resilience during these harsh times and its capacity to reinvent itself. There have also been promising initiatives to exchange national experiences and lessons learned on financial and reopening measures. Regular exchanges about national responses to the pandemic’s impact on culture have also taken place at the EU Council level since 2020.

However, these developments are just a few bright spots on a generally gloomy scene. According to ECFR’s national researchers, in at least 12 countries – as diverse as Spain, the Netherlands, Finland, Hungary, and Lithuania – the consequences of the pandemic on the cultural and creative sectors have been seriously negative. In 12 others – including France, Italy, Poland, and Slovenia – there have been temporary negative consequences, although researchers report that the cultural and creative sectors have generally managed to adapt to the situation.

For example, in France, theatres, cinemas, and concert venues were closed for 162 days in 2020. The impacts of the pandemic were felt unevenly across different sub-sectors. While cinemas and live performances lost between 43 per cent and 65 per cent of their revenue, video games and publishing benefitted from the crisis. Overall, small businesses were more strongly impacted by the pandemic. But, at the same time, measures taken by the French government – including €450m for cultural institutions and €1.2 billion to cover the cost of partial unemployment or suspended social contributions for independent workers in the sector – helped to mitigate the consequences of the pandemic. The cultural sector in many other countries fared far worse.

And still, when the next crisis hit Europe in the form of Russia’s war in Ukraine, the cultural sector once more demonstrated its resilience. In most member states, artists were at the forefront of European reaction: through concerts and cultural events organised to collect funds and show solidarity with Ukraine, but also through artistic creation such as writing songs, painting pictures, or putting on performances. For example, in Germany, the Eurovision preliminary included Ukrainian singer and former contest-winner Jamala raising €67m. In Italy, the ministry of culture initiated a campaign to remember the country’s constitutional repudiation of war and encourage the cultural sector to express its solidarity with Ukraine. These and other initiatives allowed people to connect to a shared understanding of events – and to experience grief and anger together.

However, even if the cultural sector has been especially active over these past months, it is still legitimate to ask whether it can sustainably and effectively perform its role (and help people make sense of the variety of challenges, from climate change to migration to crises of democracy) – if, at the same time, it is still having to deal with the economic consequences of the pandemic.

The question of how culture contributes to fostering European sentiment can also depend on the public cultural policies implemented in EU member states – and what they mean for freedom of cultural expression. According to ECFR’s research, in two-thirds of member states public cultural policies are used to support cultural activities with the aim of preserving or promoting local and national culture and cultural heritage. These do not necessarily stand in opposition to the idea of Europe. For example, in Portugal, cultural policies have a strong European dimension, as the country’s democratic elite have sought to orientate it towards Europe, and aim to create a contemporary Portuguese identity in opposition to the nationalism of the country’s era of dictatorship.

However, in two countries – especially in Hungary, but to some extent also in Poland – public cultural policies explicitly promote discourse that has a distinctly more nationalist flavour. This comes from strong government control of public cultural institutions and by channelling public (and corporate) funds to nationalist cultural initiatives. The criteria for appointing directors of national cultural institutions and providing funding privilege a nationalist vision. In such a context, it is becoming increasingly difficult to expect that national mainstream culture could help Hungarians (and, to a lesser extent, Poles) develop European sentiment. This concerns even the Eurovision Song Contest, which has not counted Hungary as a participant since 2019. (The other two EU members missing are tiny Luxembourg, which has not participated in the contest since 1993, and Slovakia – absent since 2012.)

Also, in both Poland and Hungary, freedom of artistic expression is under pressure – as demonstrated, for example, by the arrest in 2019 of a Polish LGBT+ activist who created an image of the Virgin Mary in a rainbow halo. The country’s then interior minister praised her sudden detention. Only in 2021 did the Polish court find her and her co-defendants not guilty of offending religious feelings.

All this warrants at least three recommendations. Firstly, while the European Commission’s Report on the Rule of Law constitutes progress in how the EU monitors developments in its member states, a corresponding monitoring mechanism is missing for cultural policies. When cultural freedom is in danger it should be as much of a concern as when media freedom, independence of the judiciary, or anti-corruption frameworks are affected.

Secondly, there needs to be a greater appreciation of (and support for) the cultural sector in the EU’s policies, including through funding. Recently, the European Cultural Foundation together with Culture Action Europe and Europa Nostra proposed a Cultural Deal for Europe. They advocated the mainstreaming of culture throughout EU policies and priority areas, from the rule of law and democracy, to the green deal and international relations. They also called for the inclusion of culture in the EU’s post-pandemic recovery funds.

There are some encouraging signs that these messages have not gone unheard. With the recovery fund, the EU institutions have for the first time mobilised extraordinary support for the cultural and creative sectors. And von der Leyen has publicly acknowledged that “Europe cannot be Europe without a thriving cultural sector”. But it remains to be seen whether such a realisation has permanently taken root in Europe’s political thinking.

Finally, the EU institutions should do a better job at publicising existing support and opportunities. For example, in Portugal, European aid for the cultural sector during covid-19 was channelled via the state, and ECFR’s research suggests it was perceived as such. Therefore, one of the things the pandemic has shown is that, within domestic cultural sectors, there is either little knowledge of European support, or European contributions simply go unrecognised. This is a missed opportunity for cultivating European sentiment.

Media

Like cultural players, the media play a crucial role not only in informing citizens but also in creating joint meanings and influencing public opinions and emotions. This is clear in today’s context of war. Print and online news, television, radio, and social media enable Europeans to follow daily what is happening in Ukraine and form their own view. Some have even called this conflict the first social media war. This state of affairs may especially favour Ukraine as social media generates international support and sympathy for the country – something that would be much harder if people were to rely mostly on traditional mainstream media reporting.

Of course, the importance of the media in affecting European sentiment has also been visible before: for example, in cases of foreign disinformation campaigns waged through the media during the 2017 presidential election in France and the 2019 election to the European Parliament – or with citizens’ interest during the pandemic in reliable data from other European countries on covid-19 infections and vaccinations. The war in Ukraine began when the realisation was already on the rise in Europe of the importance of ensuring media freedom, media literacy, and media pluralism – and of countering foreign-led disinformation campaigns.

From this perspective, it makes a big difference whether the national media (which still constitute by far the main source of information across the EU) are free – and, if they are not, whether people possess the necessary tools to identify content that they can or cannot trust. For example, state-owned media and certain pro-government outlets in Hungary have presented a highly skewed image of war in Ukraine, relativising Russia’s aggression and at times promoting conspiracy theories about the conflict. Budapest has been dubbed the EU capital of Russian disinformation. The country’s parliamentary election result was at least in part due to Orban’s control of the country’s media ecosystem.

But the fact that Hungarian citizens perform so poorly on media literacy also matters. There is a strong correlation between media freedom and media literacy, as the chart below shows. But it still makes sense to look at each of them separately. For example, Poland is – alongside Bulgaria, Hungary, Malta, Greece, and Croatia – one of the most worrying cases in the EU when it comes to media freedom. Like in Hungary, recent cases have seen the country’s journalists spied on using Pegasus software, probably by national security services. What is more, according to Reporters without Borders, there has been a major deterioration in the country’s media freedom over the past couple of years. The main problem is the capture of the public media by the ruling Law and Justice party, and the important role played by government-controlled companies in advertising, which leads to self-censorship in private media that depend on these companies for income. However, levels of media literacy are relatively high in Poland, according to Open Society Institute in Sofia (OSIS). One can thus hope that limited media freedom does not affect people’s opinions and emotions – including their European sentiment – as much as it does in Hungary.

However, the war in Ukraine is a reminder of just how important media freedom and media literacy are not just for the quality of the public debate, but also for Europe’s security. As Borrell recently observed, Russia’s war in Ukraine started long before 2022, with successful Russian disinformation efforts taking place inside the EU. Media outlets such as Russia Today and Sputnik were active across member states for many years. It is with their help that Kremlin tried – and failed – to influence France’s presidential election in 2017. They continued operating across Europe nonetheless.

In March 2022, as part of its sanctions on Russia, the EU finally banned Russia Today and Sputnik from broadcasting within the bloc. Several member states have taken additional steps. For example, Lithuania suspended the operation of six Russian and Belarusian TV channels in the country. These are all useful steps, although Reporters without Borders have warned that EU institutions banned Russian media without using an appropriate legal framework. Moreover, Russia is now working hard to use the internet to circumvent restrictions on accessing the European market.

These steps are especially important since significant Russian minorities live in member states such as Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, and they tend to use Russian-language media. And elsewhere, such as in France, Poland, Italy, and Spain – where Sputnik and Russia Today used to be present – the Kremlin-controlled media have been active in spreading disinformation. The covid-19 pandemic already showed how vulnerable people are to disinformation, as very low vaccination rates in Bulgaria and Romania (the two countries with the lowest levels of media literacy across the EU) seem to confirm. The war in Ukraine has also been accompanied by widespread disinformation across Europe: from Poland to Spain, Portugal, Italy, Austria, and Greece.

Still, part of the problem is the extent to which Russia has managed to infiltrate the European media ecosystem – with the free media inviting onto their programmes commentators who parrot Kremlin propaganda without challenge. Sometimes, they also give their floor to Russian propagandists: as was recently the case with the invitation of Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov to one of the key private TV channels in France, or Italian TV letting Sergei Lavrov use prime time to make anti-Semitic accusations.

Another problem is that not all governments will be interested in having a literate public and a free media. Indeed, there are many reasons why they would prefer exactly the opposite. But this is, again, an area closely linked to rule of law and on which the EU can and should make a useful difference. Media pluralism is already part of the European Commission’s annual rule of law reports. At the same time, the European Commission is expected to propose a new regulation later this year to tackle media independence. The pandemic and the war could well serve as eye-openers to convince national and European leaders and the public of the relevance of this problem – and of the need to take action.

Conclusion: The crucible of war

Anxiety, stress, grief, disbelief, helplessness – these feelings are widespread in Europe today, as people doomscroll the news about the fighting in Ukraine and learn about new war crimes committed by Russian troops. These dominant sentiments come in the wake of the covid-19 pandemic and all the fear and uncertainty it brought.

What does this mean for how Europeans feel about the EU these days? What do they expect from it in a world where history has not ended? The jury is still out. And, notably, there is a major risk that the current security crisis could follow a reverse logic to that observed during the pandemic – which featured a disunited reaction first followed by bold decisions later.

In the weeks immediately after the Russian invasion, it was easy to feel upbeat about the European response. Europeans not only mobilised but were also remarkably united in their solidarity with Ukraine and criticism of Russia. Member state governments and EU institutions reacted boldly and swiftly, imposing massive sanctions on the Russian economy and elites, sending military aid to Ukraine, and even raising the prospect of the country’s accession to the EU. They started working on ways to end European dependence on Russian energy imports. Several countries announced a major increase in military spending. Denmark called a referendum that could end its opt-out from the EU’s security and defence policy. What is more, the mobilisation of European citizens merits equal attention. Poland alone welcomed almost three million Ukrainian refugees in two months, with thousands of ordinary citizens involved in helping them.

This seems like the perfect moment to cement the refoundation of Europe that began in 2019. The EU has a unique opportunity to prove to its citizens that it can satisfy their rising expectations of the bloc. This would be a powerful bonding agent for the European sense of belonging.

But much can still go wrong. The current wave of solidarity with Ukraine is almost certain to subside once Europeans start feeling the economic effects of war and sanctions on Russia. International prices of fossil fuels and cereals are already hitting new highs. Even countries distant from Ukraine and that do not import Russian energy – such as Portugal – may worry about the war’s and EU sanctions’ effect on people’s purchasing power, bringing back difficult memories of the eurozone crisis.

At the same time, some Europeans might grow anxious about the number of Ukrainians who find refuge in their country. They could also start fearing that too much solidarity with Ukraine could draw their countries into the war, which they would prefer to avoid; or that helping Ukrainian refugees takes away resources that could otherwise be used to support low-income citizens. After a brief moment of rallying round the flag and of pausing domestic disagreements, politics as usual could kick back in.

On top of that, EU and member state responses to the conflict will at some stage start to be assessed on the basis of results and not just intentions. For the moment, Europe has not managed to stop the war or prevent grave war crimes. This may explain why not all Europeans are happy with what their governments and the EU institutions are doing. It is enough to attend any of the European rallies of solidarity with Ukraine to see that many are expecting even more decisive action. It is debatable whether such requests – a no-fly zone, withdrawing all business from Russia, ceasing to buy Russian gas, oil, and coal – are realistic or even reasonable. But they illustrate well the potential dissatisfaction with European policy among at least part of the population.

With calls for more action on the one hand, and a risk of waning solidarity on the other, the EU may face a double squeeze. Its leaders could conclude that it is impossible to satisfy European citizens’ expectations because they are too diverse and conflicting. But does this mean that the current moment should be dismissed as a brief carnival of solidarity and unity? Are Europeans bound to return to “before covid”, when they might be more or less happy with the EU, but it did not really matter because they did not expect much from it anyway?

It may sound trite to say so, but this is a moment of political leadership. Watershed moments do not just happen – they are made by determined leaders who understand that the sentiment of the moment can, if they act quickly and resolutely, be transformed into dramatic action – and help generate a wider sense of belonging. On such occasions, leaders need to avoid basing their decisions on short-term political calculations. Instead, they need to show responsibility and a sense of gravity, even if it risks costing them the next election.

Just as importantly: leadership is needed that does not stop at national borders and that is genuinely European. Against the habit of easy Brussels-bashing, national leaders should learn the art of praising Brussels where appropriate – and of acknowledging the value of European cooperation.

To avoid the shoals, leaders need a compass. This paper has demonstrated several dilemmas that they may face – and what consequences their choices could have. Europe’s decision-makers may be tempted to take shortcuts. Yet it would be short-sighted if leaders were to privilege the struggle against Russia at the expense of other European priorities, such as human rights and climate change. There should exist ways of reconciling them. But, ultimately, it is for politicians to choose – at least until the voters choose new leaders who possess a sense of how to address these problems.

Meanwhile, this also points to the need to not just strengthen European unity through decisions concerning security, the rule of law, climate policy, financial solidarity, and migration – but also to ensure that European sentiment can be nurtured in each and every member state. This includes through culture and the media, whose role in that process should not be underestimated. Policy cooperation alone will not suffice if it is not accompanied by sentiments and commitments on the part of the broader public.

This is particularly clear when it comes to foreign policy. As experienced observer Gijs de Vries rightly pointed out in 2019, Europe’s attachment to cultural freedom is one of the main arguments that the EU can use to effectively respond to the erosion of liberty around the world. He suggested placing cultural freedom at the centre of Europe’s cultural diplomacy. As part of its soft power, European culture and European freedoms (including that of cultural expression) are arguably among the most important elements of its power in general. This also underpins the need for the EU to preserve the rule of law at home (including on media freedom and pluralism, and on culture), rather than accept rotten compromises in the name of geopolitical unity. Doing so could ultimately go against its broader foreign policy interests.

But Europe’s other challenges are deeply cultural too. The debate about climate change policies is getting increasingly trapped in culture wars, as the gilets jaunes protests in France demonstrated. And, obviously, disagreements about migration are very much about culture too, and about how homogeneous, open, and accepting of diversity European societies should be. All in all, for people to make sense of today’s disruptions – such as covid-19 and war – and of the fast-changing world around them – such as changes in the ethnic make-up of societies, or the climate emergency – the media and the cultural and creative sectors need to assist them in that task. Meanwhile, media and culture need the freedom and resources to fulfil this purpose.

But the current moment is also deeply cultural in a different sense. Ultimately, with war in Ukraine, Europeans are facing several big and difficult questions about themselves, such as those concerning the geographical borders of Europe and the EU; or the role of culture (as opposed to economy or geopolitics) in defining what Europe means. The EU might be about to reach the limits of integrating in a depoliticised way, continuing to deploy policies and laws without properly acknowledging – or fostering – what keeps Europeans together culturally.

In this process, the EU’s purpose may also be about to change. Europeans might realise that their project, despite all the teleology of an “ever closer Union”, was largely focused on the past – and on making war obsolete. This goal has been achieved among its member states. But the memory of a past tragedy was already becoming less useful as a unifying factor: according to Eurobarometer data from the past decade, EU citizens associate the bloc mostly with its freedoms rather than with peace.

Some may argue that war in Ukraine has brought things back into proportion – that it makes Europe’s founding narrative as relevant as ever. If war makes the state as much as the state makes war, one might wonder how much of a state-making impetus the war in Ukraine, and Europeans' involvement therein, could mean for the EU. Because of this war, the EU might indeed choose to invest more in its defence, security, and foreign policy cooperation. But this should not be the main lesson the EU draws from this crisis.

Paradoxically, with the re-emergence of war in Europe, the EU’s time as principally a peace project might be coming to an end. This provides a new opening – and thus requires creativity. From fighting climate change, to defending freedom, the rule of law, and human rights, to showing solidarity with one another – the EU has a unique chance to prove its citizens, and the rest of the world, that Europe is about so much more. This time, culture will need to be at the centre of that endeavour.

Country dashboards

About the author

Pawel Zerka is a policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations. He is part of ECFR’s Re:shape Global Europe project, which seeks to develop new strategies for Europeans to understand and engage with the changing international order. He is also engaged in the analysis of European public opinion as part of ECFR’s Unlock Europe’s Majority initiative, and in research into Europe’s economic statecraft. He also works on Polish, French, and European foreign policy.

Zerka holds a PhD in economics and a master’s degree in international relations from the Warsaw School of Economics, having also studied at SciencesPo Bordeaux and Universidad de Buenos Aires. He is based at ECFR’s Paris office and has been part of the ECFR team since 2017.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the European Cultural Foundation – especially André Wilkens, Isabelle Schwarz, and Tsveta Andreeva – for their trust and interest in developing the European Sentiment Compass as a joint ECFR-ECF initiative.

This project is largely based on research conducted by ECFR’s 27 associate researchers, whose hard work under extremely tough deadlines needs to be recognised: Sofia Maria Satanakis, Vincent Gabriel, Marin Lessenski, Robin Ivan, Huseyin Silman, Vladimir Bartovic, Christine Nissen, Viljar Veebel, Salo Mathilda, Gesine Weber, Jule Koenneke, George Tzogopoulos, Zsuzsanna Vegh, Isabella Antinozzi, Aleksandra Palkova, Justinas Mickus, Tara Lipovina, Danny Mainwaring, Niels van Willigen, Adam Balcer, Lívia Franco, Oana Popescu, Matej Navratil, Marko Lovec, Astrid Portero and Ylva Pettersson

The author is also grateful to ECFR colleagues – in particular, Susi Dennison, Jenny Söderström, Jeremy Shapiro, and Anthony Dworkin – for supporting the project from its inception. Rafael Loss read an early draft and made useful suggestions (including to quote Charles Tilly). Tara Varma brought to attention the need to underline the importance of how EU decisions impact on the bloc’s perception among the non-members.

Special thanks go to Mick Jonkers for research assistance, Chris Eichberger and Marlene Riedel for graphic design, and Juan Ruitiña for his coding magic and placing everything online, as well as Andreas Bock, Swantje Green, Mathilde Ciulla, and Amandine Drouet for being full of ideas and initiative on the advocacy side of the project. Finally, having Adam Harrison as editor was a luxury that most authors can only dream of.

Any mistakes or omissions are the author’s alone.

The European Sentiment Compass is a joint project and initiative by the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR) and the European Cultural Foundation (ECF).

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.