Faltering fightback: Zelensky’s piecemeal campaign against Ukraine’s oligarchs

Summary

- Ukraine’s president, Volodymyr Zelensky, has declared a “fightback” against oligarchs.

- Zelensky is motivated by worries about falling poll ratings, pressure from Russia, and a strong desire for good relations with the Biden administration.

- The fightback campaign has resulted in action against some oligarchs but, overall, it is incomplete.

- The government still needs to address reform issues in other areas, especially the judiciary, and it has an on-off relationship with the IMF because of the latter’s insistence on conditionality.

- The campaign has encouraged Zelensky’s tendency towards governance through informal means. This has allowed him to act speedily – but it risks letting oligarchic influence return and enabling easy reversal of reforms in the future.

Introduction

On 12 March this year, Ukraine’s president, Volodymyr Zelensky, released a short appeal on YouTube called “Ukraine fights back”. He declared that he was preparing to take on those who have been undermining the country – those who have exploited Ukraine’s weaknesses in particular, including its frail rule of law. He attacked “the oligarchic class” – and named names: “[Viktor] Medvedchuk, [Ihor] Kolomoisky, [Petro] Poroshenko, [Rinat] Akhmetov, [Viktor] Pinchuk, [Dmitry] Firtash”. He proceeded to address the oligarchs directly, asking, “Are you ready to work legally and transparently?” The president went on, “Or do you want to continue to create monopolies, control the media, influence deputies and other civil servants? The first is welcome. The second ends.”

Ukrainians have heard this kind of talk before. Zelensky’s predecessor, Poroshenko, also made ‘de-oligarchisation’ a policy pledge. So, is this Groundhog Day, with the same empty promises, or is anything different this time? The signs are that some change may now be afoot in Ukraine, although it is proceeding in fits and starts, and with no small number of setbacks. And Ukraine’s international situation is having a significant influence over this.

In embarking on this campaign, Zelensky is certainly seeking to strengthen his position against domestic challengers, but his most recent high-profile step – a new ‘anti-oligarch bill’ presented to parliament on 1 June – reveals the important external dimensions of the president’s declared “fightback”. The cumbersome full title of the new bill is: “On the prevention of threats to national security associated with the excessive influence of persons of significant economic or political importance in public life (oligarchs)”. The wording reveals that Zelensky’s démarche is as much about strengthening Ukraine’s national security and handling its relations with Russia as it is about taking on corruption and improving his own standing. Since the start of the year, Russia has increased its pressure on Ukraine, leading Zelensky to seek help from the United States. And the arrival of the Biden administration means that, to receive American help, Zelensky must reduce his ties to his traditional oligarch partner, Kolomoisky, who is now under US sanctions. Once again, moves by Russia and the US have a direct influence on Ukraine’s domestic political trajectory.

Ukrainian politics has long been dominated by oligarchs, however, and Zelensky has a lot of ties to cut. For most of 2020, Ukraine was slipping in the other direction, with rising oligarchic influence rolling back the president’s earlier reforms, and even those of the Poroshenko era. Therefore, Zelensky’s portrayal of the new measures as an “anti-oligarch crusade” is implausible. And the coronavirus crisis could still undermine any novel efforts in this area – the pandemic has already pushed Ukraine in both directions: the country needs help from the European Union on vaccines and restoring free movement but, in a more isolated Ukraine, oligarchs have sought to embed their interests while the world is distracted. Zelensky himself embodies these contradictions. Ukraine under the comedian president is a multiverse, where different interests and realities coexist and constantly collide. But if Zelensky enacts enough reforms – whatever his motivation – then the influence of the oligarchs will decline.

Zelensky since 2019: Steps forward, steps backwards

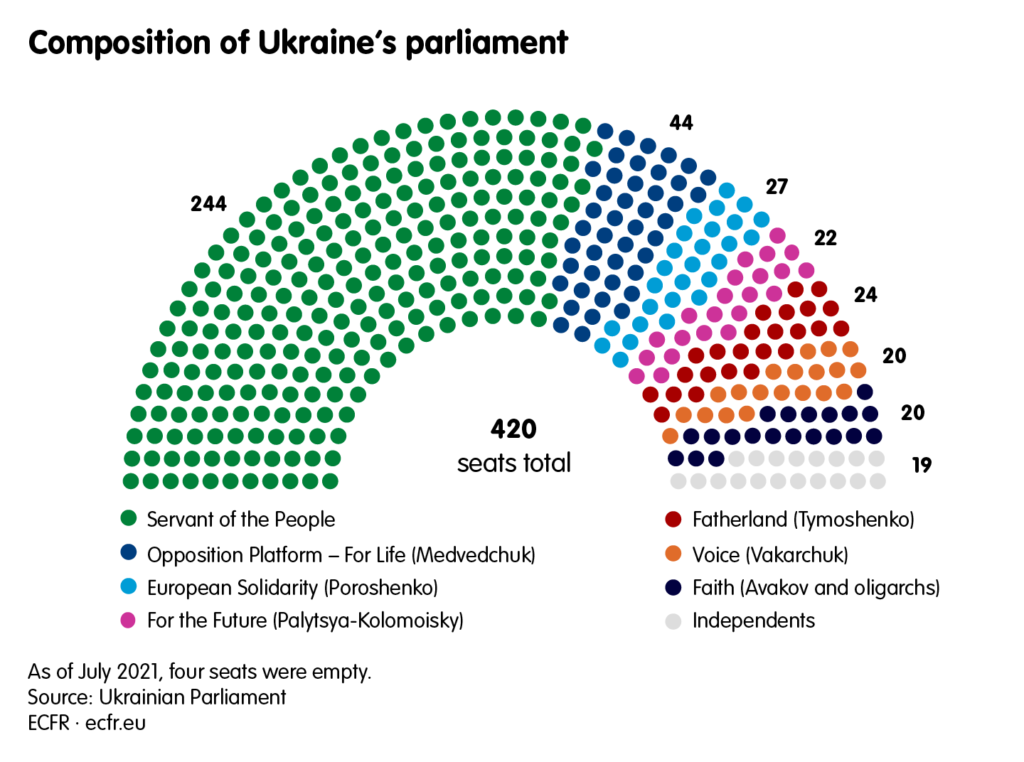

Zelensky’s presidency has been characterised by progress and followed by regression in taking on oligarchic influence. His term can be divided into three phases. The first came after his landslide victory with 73.2 per cent of the vote in April 2019, in which he promised both reform and peace with Russia. However, Zelensky had to coexist with the parliament elected under Poroshenko until July that year, when his Servant of the People party won 254 out of 424 parliamentary seats.

In the second phase, Zelensky’s first prime minister, Oleksiy Honcharuk, ran something of a hybrid government between August 2019 and March 2020. Oligarch-based revanchist forces – openly hostile to reform and friendly to Russia – coexisted with reformers. Libertarians and e-government enthusiasts pushed innovative changes. The government implemented several key ‘hangover’ measures on which the Poroshenko administration had dragged its feet, including a reset of the National Agency on Corruption Prevention (NACP) and the unbundling of the national oil and gas company, Naftogaz. Progress was even made in some previously corrupt or reform-resistant areas. Most notably, the new prosecutor general, Ruslan Ryaboshapka, was starting to have some success in cleaning up the Prosecutor General’s Office.

There was shock, therefore, when the president replaced not just Honcharuk but most of the government in March 2020. This third phase was in large part initiated by the oligarchs, who thought that Zelensky’s early reforms and Ukraine’s – at the time – accelerating economic growth would allow for a more autarchic approach. This would have been to their advantage, with less interaction with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and de facto less integration with the EU. Equally, Russia spied an opportunity to rebuild its propaganda networks and pro-Russian forces in Ukraine, in particular the Opposition Platform, which had come second in the 2019 parliamentary election. Many oligarchs also saw bandwagoning with anti-EU and anti-American propaganda as a good way of protecting their interests from reformist pressure.

In 2020 the government became tangled up in an affair that threatened to make it look overly pro-Russian – to the dismay of many reformers and pro-European voters.[1] Last summer, Ukraine was planning an operation to lure 33 members of Russian mercenary group Wagner to Kyiv and arrest them; the men were accused of war crimes in Donbas and elsewhere. But the operation was compromised, allegedly by people in Zelensky’s inner circle who wished to avoid confrontation with Moscow. The president’s chief of staff, Andriy Yermak, then reportedly tried to stop a Bellingcat investigation into the affair, including by pressuring the deputy head of British intelligence agency MI6 when he was in Kyiv. These revelations weakened Zelensky’s position in the eyes of ‘patriots’.

Against the backdrop of this scandal and a new government characterised by anti-reform forces, the president tried to maintain ‘balance’ by promoting a banking law that would prevent the return of insolvent banks to former owners and thus run counter to oligarchic interests. Kolomoisky wanted compensation for the nationalisation of PrivatBank (which he part-owned) in 2016, although there was a slew of legal cases claiming that he was responsible for $5.5 billion that had gone missing from the company.

Still, the new prime minister, Denys Shmyhal, presided over a purge of most reformist ministers and of senior figures at the highly respected National Bank of Ukraine (NBU). The Prosecutor General’s Office under the newly installed Iryna Venediktova began what looked like vindictive and selective prosecutions against Poroshenko, his associates from International Capital of Ukraine bank, and former NBU managers. At one stage, Poroshenko faced no fewer than 21 charges. The Prosecutor General’s Office and the judiciary rehabilitated many key figures from the era of Viktor Yanukovych, who was ousted as Ukraine’s president in the 2014 revolution. For example, the discredited former chief prosecutor Svyatoslav Piskun became a “personal adviser” to Venediktova. The new prosecutor general was lukewarm, at best, about the attestation process (reviews of prosecutors’ fitness to serve) that she inherited. During this period, civil society had less of a voice and, according to one analysis, “a number of [tainted] prosecutors [were] reinstated”.

In this third phase of Zelensky’s presidency, revanchist forces were strengthened by the rise of pro-Russian oligarch Medvedchuk’s growing media empire. By the time of the 2019 election, he was the 47th richest person in Ukraine, with estimated assets of $133m, up 70 per cent in just one year. By 2020 Medvedchuk controlled three television news channels: 112 Ukraine, NewsOne, and ZIK. In June 2020 it was revealed that he also owned one-quarter of 1+1, Ukraine’s most popular television channel, the rest of which belongs to Kolomoisky. Medvedchuk also had a big presence on social media, backed by Russian trolls and bots. And his growing empire was only the core of an entire media ecosystem that included attack websites such as strana.ua, the vlogger Anatoliy Shariy and his political party, and former figures from the Yanukovych era.

This virtual chorus pushed out increasingly strident propaganda attacking the EU and accusing Ukraine of being a failed state. It spread myths of “external governance” and the EU “curation” of Ukraine, while depicting reformers as self-interested Sorosyata (puppets of George Soros) – a view that has some traction among Zelensky’s inner circle.[2] The network also shared coronavirus disinformation. Furthermore, the channels had learned from the 2014 revolution that an openly pro-Russian message did not sell; instead, they relentlessly promoted the agenda of ‘peace’ in the east and sought to undermine the rationale for the war there, which they blamed on foreign pressure and corrupt local interests rather than on Russia.

Meanwhile, Ukraine’s economy was hit hard by covid-19, and there were no vaccines in sight until late spring 2021. In fact, parliament voted against accepting any Russian vaccine in January. Relations with the IMF were deteriorating, despite constantly over-optimistic noises to the contrary from Kyiv. Overall, Zelensky looked isolated at home and abroad: his first chief of staff, Andriy Bohdan, accused his successor, Yermak, of keeping the president in a “warm bath” – only giving him good news. But this could not last forever. Zelensky’s party, Servant of the People, had dropped to third place by early 2021, while the strengthened propaganda empire of the oligarchs was driving up the popularity of the Opposition Platform, which was jointly led by Medvedchuk, who has a seat in parliament. At the start of the year, pollsters SOCIS and KIIS measured Servant of the People’s support as standing at 17.6 per cent, with the Opposition Platform and Poroshenko’s European Solidarity both slightly ahead. Zelensky was still the most popular leader, on 25.6 per cent – six percentage points ahead of his nearest challenger, Poroshenko. Even so, the domestic picture looked uncertain for the president.

Ukraine’s international position

This general nadir extended to Ukraine’s international relations. The peace process was going nowhere, which made the Russia-supported ‘peace lobby’ in Ukraine look ever more like a Kremlin mouthpiece. Moscow’s efforts to get Kyiv to talk to “representatives” of the “Donetsk People’s Republic” and the “Luhansk People’s Republic” failed to make progress in the autumn. And Zelensky seemed to have gone off the idea, after initially showing some interest in it. The president attempted to revive the Normandy format, relying heavily on his personal charisma in interactions with other leaders, which at least led to good mood music at a Paris summit in December 2019; but further meetings were stymied by the pandemic.

In dealing with the war, Zelensky had initially preferred to concentrate on humanitarian issues, but moves such as prisoner exchanges were relatively one-sided and did nothing to change the diplomatic calculus. Few Western powers were paying Ukraine close attention: France under Emmanuel Macron continued to push for a broader reset with Russia, and both France and Germany remained deaf to Ukraine’s calls to reformat the Normandy process. In Ukraine, there was much disillusionment with Europe.

However, the outcome of the November 2020 presidential election in the US changed calculations on all sides and set the wheels in motion in Ukraine that led to the fightback. Expecting a tougher time from Joe Biden, Russia sought to test the mettle of the new administration in Washington and forestall any Ukrainian rapprochement with the US. By spring 2021, Russian escalation involved the massing of at least 100,000 troops on the Ukrainian border and a renewed partial blockade of the Sea of Azov.

Ukraine and the US

International pressure has often been essential to the success of reform efforts in Ukraine, which has made progress as a state only when domestic reformers have allied with the US and the EU to push back against powerful vested interests. Criticism of foreign “curation” of Ukraine is often sponsored by oligarchs to protect their own positions.

For Ukraine, the Trump era was paradoxical. On the one hand, the country was sucked into Trump’s first impeachment and Rudy Giuliani’s search for dirt on the then president’s political rivals. On the other hand, there was no pressure to reform. In that sense, Ukraine had an easy time under Trump. And this backdrop helped the oligarchs regain strength in Zelensky’s third phase in office.

But, once Biden became president, Zelensky and his team knew that they would need to repair the relationship, which had been badly damaged by the Giuliani affair. They hoped for a dramatic improvement in relations, given that Biden knows Ukraine well and wanted to shift the narrative away from the Ukrainian ‘scandal’ involving his son. But Ukraine first had to deal with the seven Ukrainians sanctioned by the US over Giuliani’s activities: MP Oleksandr Dubinsky, former Ukrainian official Oleksandr Onyshchenko, local ‘fixer’ Andriy Telizhenko, and media mogul Andriy Derkach and members of his team. These were not Ukrainian state actors, but there was still a need to make amends, particularly for the 2020 propaganda theme #demokoruptsiya (‘demo’ being the US Democrats) on social media, which was most prominent on media outlets owned by Medvedchuk and Kolomoisky. Biden took his time making his first phone call to Zelensky, a delay that caused much nervousness in Kyiv and was a message that Ukraine had to deliver on reform.

The US and others – notably the United Kingdom – supported the moves against Medvedchuk when they came, but Washington still held back from sending more general signals of support. When the phone call between Biden and Zelensky finally took place on 2 April, they only discussed security, given the Russian troops massed on Ukraine’s borders. The US secretary of state, Antony Blinken, visited Kyiv on 6 May. It was important just to turn up, but the outlines of a more general approach – of enhanced security for enhanced reform – remained vague. Blinken offered little that was concrete. Instead, the US abandoned most of its opposition to Nord Stream 2, in advance of Biden’s meeting with Vladimir Putin on 16 June; this left Ukraine exposed to the loss of fees for gas transit across its territory, amounting to between $2 billion and $3 billion in annual revenues. And neither Ukraine nor Georgia was invited to the NATO summit on 14 June, which left Zelensky looking as though he had overshot in ramping up his rhetoric on Ukraine’s need for a NATO Membership Action Plan (MAP). But the US compensated by offering him an official visit to Washington in summer 2021.

In short, the international pressure was back on for Ukraine to reform, and to be seen to reform. Early moves to respond to this US priority may have motivated Russia to begin sending its troops to the border with Ukraine, as moves against some oligarchs began. Pressure from Russia may also explain the partial and incomplete nature of the fightback so far. Ukraine’s multiverse never exists apart from its international context.

The fightback

To understand more about the success or otherwise of the fightback campaign, it is worth knowing a little more about some of the key figures involved. Two key targets are Medvedchuk and Kolomoisky. Medvedchuk appears to have been made the primary figure in the campaign, with Kolomoisky figuring to a lesser extent. With both, however, it is not apparent that the fightback is as comprehensive as the rhetoric around it would suggest.

Viktor Medvedchuk

Medvedchuk is the former chief of staff to Leonid Kuchma, Ukraine’s second president following independence. Despite being Russia’s main agent of influence in the country, Medvedchuk has long been able to operate with impunity in Ukraine – at least until the recent actions against him. As noted, he is currently a member of parliament for the Opposition Platform, and Putin is the godfather of one of his two daughters. Under Poroshenko, Medvedchuk built up a television empire that would attack Poroshenko – but also his opponents on occasion. It was rumoured that Poroshenko saw him as a convenient, ultimately unelectable, opponent. And a call by parliament in 2018 to sanction pro-Kremlin media outlets, especially those owned by Medvedchuk, went unheeded by Poroshenko. In Zelensky’s first year and a half, Medvedchuk offered the possibility of influence on Putin and progress in the Normandy format talks.

But, in February 2021, the National Security and Defence Council (NSDC) – which is headed by Zelensky – kicked off the anti-oligarch ‘campaign’ by announcing sanctions against Medvedchuk and his wife, accusing him of financing terrorism in east Ukraine. The NSDC ordered the closure of Medvedchuk’s three main television channels and imposed sanctions on their nominal owner, Taras Kozak, although they remained available online as late as April. Given Medvedchuk’s past impunity – which many of Ukraine’s foreign friends raised questions about even during the Poroshenko presidency – this was seen as a serious, potentially game-changing development. But, on closer inspection, the move against Medvedchuk was less about a general anti-oligarch campaign than the context of the stalling Normandy process and Zelensky’s falling opinion poll ratings.

Despite the headline news, only three out of around 100 entities owned by Medvedchuk were sanctioned; most of his more successful assets were untouched. The big exception was the oil pipeline PrykarpatZakhidTrans. Since the war with Russian-backed forces began in 2014, Ukraine has stopped importing Russian gas. Russian oil, however, has continued to flow. Lucrative covert oil deals with Russia have helped pay for Medvedchuk’s media empire. So, the seizure of the pipeline from his portfolio was important from the perspective of national security and energy self-sufficiency; but there have been rumours that the state might eventually hand the pipeline over to Kolomoisky. It is, therefore, unclear whether the government has really embarked on a campaign to take key infrastructure assets out of the hands of oligarchs.

In response to the moves against him, Medvedchuk initially attempted to circumvent the television ban by setting up a new media company, Novyny, and a television channel, First Independent. These had many of the same managers and journalists, the same business address, and – most importantly – the same propaganda narratives. But Medvedchuk’s attempts were blocked by most online platforms. Some of his audience has migrated to another pro-Russian channel, Nash (“Ours”).

A partial victory for Zelensky has been the softer tone adopted by a much bigger channel, Inter, traditionally also full of anti-Western and ‘pro-peace’ rhetoric. The prominence of foreign policy motivations in the fightback can also be seen in the creation by the NSDC of an International Centre for Countering Disinformation, and sanctions issued against other Russian channels, including ITAR-TASS, Russia Today, and Gazeta.ru.

One interpretation of Russia’s troop build-up on the Ukrainian border in spring 2021 was that it was a response to the pressure on Medvedchuk. This might explain why Zelensky’s team held off further moves against him until tensions eased in May. But, on 11 May, Medvedchuk and Kozak were formally charged with treason, including extra charges of appropriation of natural resources in occupied Crimea.

But, at the least, the Opposition Platform may now find it difficult to sustain its levels of support without television channels.[3] Indeed, polls conducted in April showed the Opposition Platform had already fallen to third place.

Ihor Kolomoisky

If Zelensky’s anti-oligarch campaign was to have more general credibility, the key test was his long-standing association with east Ukrainian oligarch Kolomoisky. Zelensky’s television shows were broadcast on Kolomoisky’s 1+1 channel, and the oligarch was his main backer in the 2019 presidential election. Crucially, Kolomoisky was also linked to the furtive strategy to help supply Giuliani with kompromat on Biden and his son. This seems to have been the key factor in the timing of Zelensky’s team, which began to act against Kolomoisky shortly after Biden’s victory in November and accelerated its work in January. Meanwhile, in 2020, Kolomoisky had strengthened his informal control of Centrenergo, which is Ukraine’s most lucrative energy distribution company. When the Honcharuk government tried to change Kolomoisky’s managers in February 2020, the new managers were physically harassed and Honcharuk fell instead. A Kolomoisky company continued to sell coal from state mines to Centrenergo, and other companies receive its electricity at a huge discount. As an oligarch who had appeared to emerge unscathed from Zelensky’s anticorruption efforts, Kolomoisky was a target that the Ukrainian government had to pursue to demonstrate its reformist credentials to the US.

On 22 February this year, a key executive from PrivatBank, Volodymyr Yatsenko, was arrested at Kyiv airport. Shortly afterwards, the US “designated” Kolomoisky for his involvement in “serious corruption”. On 15 March, prosecutors charged Yatsenko and two other senior PrivatBank executives with embezzling $300m. Five weeks later, Kolomoisky’s company offices in Kyiv were searched in connection with the alleged embezzlement of $8m from Centrenergo. But, as with Medvedchuk, the core of Kolomoisky’s empire continues to operate. According to Honcharuk before his fall, “one moment we fight against Kolomoisky, the other we don’t.”[4] The same appears to be true even now, amid the purported fightback campaign.

Other figures

Not all those on Zelensky’s original list of “oligarchs” have been targeted equally. Medvedchuk and Kolomoisky appear to have been singled out, while additional tax changes that would affect the business empires of Akhmetov and Pinchuk have yet to be enacted (see below). Other controversial powerful figures continue to act unrestrained, especially Arsen Avakov, the interior minister, who has pushed some reforms and blocked others. In fact, Avakov has amassed so much power that he is arguably the second most influential person in the country.[5] He shields Zelensky from so-called radical nationalists, disgruntled war veterans, and the Poroshenko old guard. Conversely, he is also a lightning rod for popular discontent. But Zelensky’s behaviour falls into a general pattern of failing to restrain bad actors or support independent reformers.

That being said, two other oligarchs were added to the list on 18 June: Firtash and Pavel Fuks. Firtash was enmeshed in the Giuliani scandal, but was sanctioned for allegedly selling titanium products to the Russian defence sector, rather than for his role in Ukrainian politics and business.

Meanwhile, in February, rumours of moves against the Priamyi television channel had led to Poroshenko pre-emptively buying the channel himself. (Priamyi was already widely known to be Poroshenko’s channel, despite the fact that politician Volodymyr Makeyenko was the nominal owner). But, as an owner, Poroshenko could now be the victim of the new anti-oligarch bill, whose measures could be used by Zelensky to ‘cleanse’ the media space of his political opponents.

One noteworthy aspect of the measures in 2021 is that many have been channelled through the NSDC, which Zelensky appears to be using to take action against oligarchs (even if this action remains somewhat limited in scope). One senior EU official reports that the NSDC appears to be an effective means for Zelensky to counter Russia, enabling him to link up external policy and internal policy to deal with the hybrid nature of the war.[6] The president has also likely alighted on the NSDC because the courts would have blocked any moves against Medvedchuk, who would have been able to buy protection in the corrupt judicial system.[7] The strategy of channelling everything through the NSDC rather than the courts, which is credited to Avakov, has allowed Zelensky to move with some speed. Such use of the NSDC is, however, legally dubious and forms part of an alarming trend towards the securitisation of political issues and the marginalisation of existing institutions and norms. The NSDC has provided no definition of what should and should not be sanctioned, or of Medvedchuk’s supposed treason, or of Russian propaganda. Its selective use is part of the incomplete nature of what ought to be a generalised anticorruption effort.

Judicial reforms stalled

In May 2021, the Venice Commission issued a report critical of Ukraine’s proposals to reform the High Council of Justice. Indeed, the country has much work to do on this front. The inadequacy of reform in the judicial realm – reflected in a crisis triggered by the Constitutional Court, many of whose members were well known for their links to oligarchic sponsors – is the motive for another element of Zelensky’s fightback speech.

Firstly, in July 2020, the court declared unconstitutional the appointment in 2015 of Artem Sytnyk as head of the National Anti-Corruption Bureau of Ukraine (NABU). The creation of NABU was one of the success stories of the Poroshenko era; but, in this way, the body began to come under open attack by revanchist forces.

Such forces also targeted reformist NGOs. A civic activist from the city of Odessa, Serhiy Sternenko, was accused of murder while defending himself from physical attack, and he was framed by Russian and local media as a radical nationalist. In February 2021, an Odessa court sentenced Sternenko to seven years and three months in jail. This crisis deprived Zelensky of the opportunity to tell a positive story of ongoing reform: the Sternenko affair meant he could no longer credibly claim that good things were happening in some parts of the Ukrainian multiverse.

Secondly, in September 2020, the Constitutional Court made a further move against NABU when it declared that key provisions of the law that created the body were unconstitutional. In particular, the court ruled against the president’s right to form NABU by decree and his role in selecting its leadership. And a further decision by the Constitutional Court in October 2020 gutted another key Poroshenko-era reform: the compulsory e-declaration of assets by state officials. The court ruled against open access and the control and full verification of declarations. It also stripped the NACP of nearly all its authority, particularly in relation to e-declarations. Collectively, therefore, much of Ukraine’s post-2014 anticorruption programme was now gone or was under threat. The court had ruled against the NACP following an appeal by 47 MPs – 44 of whom belonged to the Opposition Platform, who appeared to hope that derailing Ukraine’s anticorruption agenda would help rupture relations with the West.

Zelensky reacted to the challenge to his authority. A bill was introduced into parliament in February 2021 that would give Zelensky the power to hire and fire NABU’s head, instead of an independent commission granting seven-year terms to new appointees. More broadly, the president’s initial plan had been to dissolve the entire Constitutional Court – but this went around in circles. In December, the president then tried to suspend Oleksandr Tupytsky, the court’s chief judge. In March 2021, after this effort failed, he instead dismissed Tupytsky, arguing that his appointment was illegitimate as it had been made by Yanukovych in 2013 (just before the protests in Kyiv that led to the revolution). But Constitutional Court judges serve a fixed nine-year term, and there is no provision for removing them. Since that time, Zelensky has sought to exert informal control over the Constitutional Court: as of May 2021, the court had a new “acting chair” and Tupytsky’s salary has been cut off.

On the more positive side of the ledger, the government has picked up some earlier stalled judicial reform attempts, despite senior figures’ reluctance. For example, the 2020 attestation of the Prosecutor General’s Office dealt with all of Ukraine’s 11,000 prosecutors. They were tested on competence, knowledge, and integrity, and could fail in any of these areas. Only 7,000 survived. This was a major reboot and a “necessary shock to the system”, according to one EU official based in Kyiv.[8] Venediktova, as the new chief prosecutor, was reportedly not keen on overseeing this process, “but couldn’t make it go away”, according to one EU official, because of heavy support from the EU and the US.[9] A similar attestation model has been applied to 8,000 customs officers.

That said, Zelensky made little effort to deal with another major scandal of judicial corruption, one involving the head of the Kyiv Administrative District Court, Pavlo Vovk. The controversial court is the heart of Ukraine’s “judicial mafia”. Vovk had boasted about his “political prostitution” and his connections with Avakov, which he suggested gave him de facto immunity. Unlike with the Constitutional Court, a decree to abolish the Kyiv court was feasible; but Zelensky demurred. Only in April 2021 did he belatedly back a bill to abolish it, thereby shifting responsibility to parliament. This is a further example of the extent of the power and influence wielded by Avakov, who is also thought to have deliberately blocked much-needed reform of the police.

A general judicial reform should be one of Ukraine’s top priorities but, following the dismissal of the Honcharuk government, a challenge to the president’s political authority emerged as the oligarchs regained their strength. Yet this lack of reform was a problem of Zelensky’s own making. Despite constant urging from the EU and the US, he failed to make judicial reform a priority and allowed the oligarchs to undermine him via the courts.

Moreover, as with the increase in governance through the NSDC, Zelensky has presided over the rising informal power over the courts of people linked to the old Yanukovych administration. Their connections have helped Zelensky consolidate his power. Firstly, there was Kolomoisky lawyer Andriy Bohdan, mentioned earlier, who was Zelensky’s original chief of staff, and Andriy Portnov, the former ‘curator’ of the legal system under Yulia Tymoshenko and Yanukovych, who was in exile in Russia from 2014 to 2019. As one observer has noted, “the media often refer to him [Portnov] as the ‘grey cardinal’ of the judiciary. In fact, he is a kind of ‘corruption manager’ who controls loyal courts.” Now, there is Andriy Smirnov, who is deputy head of the Presidential Administration and has links to former Party of Regions figures such as Olena Lukash. Smirnov is also close to Avakov. According to one Ukrainian expert, “with Smirnov, a general judicial reform is unlikely.”[10] The fightback campaign has seen some progress in the judicial arena, but much remains to be done.

It is worth reflecting on the reasons why Zelensky has been making greater use of the NSDC. One key motivator is that his Servant of the People party no longer has a reliable majority in parliament.

Since the 2019 election, Kolomoisky is said to have expanded his control to 20-40 MPs within Servant of the People, effectively depriving it of a stable majority. Although Zelensky could turn to pro-European parties such as European Solidarity and Voice to get measures through, the president has regularly attacked Poroshenko since taking office, and so that approach may be unviable; Voice also suffered a series of splits in June 2021, making it a less useful potential partner.

To deal with this, Zelensky has often chosen to create an alternative majority with the two factions artificially created by oligarchs following the parliamentary election: For the Future and Faith, and the ‘Independent’ group, which is independent of party discipline but not of oligarchic influence. The three groups have 61 votes in total. Kolomoisky may control up to 70 MPs overall, dispersed across several factions; rival oligarch Akhmetov now controls up to 100 MPs. Most have been bought since the 2019 election. He has, therefore, been tempted to bypass parliament instead. This approach enables him to circumvent the oligarchs’ blocking power. But it means yet more informal politics – which is a way for oligarchs to force their way back in – as such changes lack the durability of legislation.

Partial reforms

There have been reforms in other areas, although they usually bear the signs of Ukraine’s multiverse, as the government has only implemented some of their aspects properly.

In late January 2021, an important bill on reforming the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) passed its first reading. The SBU has extensive powers and – despite intense pressure from the EU, NATO, and the US – has undergone no significant reform since Ukraine’s independence. The SBU bill in parliament, however, would tackle many of the characteristics of the organisation that have earned it a reputation as a Soviet legacy institution.[11]

The law envisages downsizing the SBU from 30,000 personnel to 17,000. The service would lose its responsibilities for smuggling and other forms of economic crime, and would be partially demilitarised. Responsibility for economic crime would be transferred to a new Bureau of Economic Security (BES). Zelensky signed the bill to create BES on 22 March; its main functions will combine analysis and enforcement. This should bring an end to the SBU’s notorious Directorate for Combating Corruption and Organised Crime, known as “Directorate K”. Far from challenging organised crime, Directorate K has a reputation for corruption and for shaking down local businesses. A second reading of the SBU bill is planned for this month. Despite criticism from some Ukrainian NGOs that the bill does not go far enough to deal with the SBU’s alleged human rights abuses, G7 ambassadors to Ukraine have called it a “major step forward”.

In April 2021, the NSDC removed 100 workers in the customs service, including 17 heads of customs. Seventy-nine companies, including 11 Russian legal entities, were sanctioned. But figures with apparent elite protection such as Elijah Pavlyuk were untouched. Smuggling is estimated to cost the Ukrainian government 300 billion hryvnia ($10.8 billion) every year. On 23 April, Zelensky responded to EU pressure by introducing a bill to amend the criminal code to recriminalise smuggling, which was controversially decriminalised under Yanukovych in 2012.

There was a flurry of legislative activity in late June 2021 as the Zelensky administration attempted to tick some more boxes before the Biden summit. One new law would strengthen the NBU and its supervisory functions, although it was passed at the same time as further members of the old reform team were leaving the bank. Another law would threaten jail to officials who made false asset declarations. A further measure restarted work on the reform of one key judicial institution, the High Qualification Commission of Judges, and gave international experts a role in the body’s formation. Some other reforms may be passed in time before Zelensky’s Washington visit, including the SBU and NABU bills, and there may be a new role for international experts in the formation of the High Council of Justice, which is the ultimate repository of judicial power.

Anti-reform forces

Meanwhile, there has been no generalised clearout of anti-reform actors since the start of the fightback, and some have even prospered. For instance, Ukraine’s health minister, Maksym Stepanov, has ridden out criticism of his slow response to the pandemic and procurement scandals, concentrating instead on media wars against his opponents.

Elsewhere, the head of Naftogaz, Andriy Kobolyev, who had long been supported by the EU and the IMF, was dismissed in April after the state-owned enterprise made a loss of 19 billion hryvnia ($684m), mainly due to the recession. But he had also spent seven years reforming what used to be Ukraine’s most corrupt state-owned enterprise. His dismissal was only possible because the government arbitrarily suspended the Naftogaz Supervisory Board for two days, prompting complaints from G7 ambassadors that this was a setback that would lead to direct control of state-owned enterprises, and would undo gains made in good governance practice. Kobolyev warned of increasing corruption risks after his departure. At the same time, Herman Halushchenko, the controversial vice-president of Energoatom, was made energy minister. His mission was the “return of national tariffs”. This is a euphemism for reverting to populist and corruption-generating subsidies rather than market pricing – an ideal setup for oligarchs to exploit.

The IMF

Ukraine’s relationship with the IMF casts further doubt over the firmness of intent behind the latest anti-oligarch drive. If the Ukrainian government was sincere about reform, it would be reconnecting with the IMF. Instead, it is doing everything it can to get away from the organisation’s conditionality approach, which would hold the Ukrainian government accountable for greater progress on transparency and the rule of law. In May 2020, the IMF Executive Board approved a $5 billion 18-month stand-by arrangement to help Kyiv deal with covid-19. Ukraine received an immediate tranche of $2.1 billion. But a long review mission from December 2020 to February 2021 led to a dismal assessment of the country’s record on corruption. Relations are now on pause and no immediate further payments are likely.

Instead, Ukraine has sought to raise money from bond issues. It raised $2 billion in July 2020, $600m the following December, and $1.25 billion in April 2021. This is worryingly similar to the strategy pursued by the Yanukovych administration in 2011-13. It could even be encouraged by the IMF’s general plan to increase special drawing rights by $650 billion to help poorer countries deal with the pandemic. Ukraine’s share would be more than $2.7 billion – in effect, the country would receive the money without meeting the IMF’s conditions.

The anti-oligarch bill

One notable addition to Zelensky’s apparent fightback was the anti-oligarch bill introduced in June 2021. The bill defines an oligarch as anyone who meets three out of four criteria: someone who “participates in public life”; someone “who has a significant impact on the media”; someone who is the “ultimate owner (controller) of” local monopolies; and someone with “confirmed assets” of one million times the national subsistence minimum, which works out at $83m. The first criterion would encompass almost everybody in public life. The fourth would include more than a hundred individuals.

Zelensky’s biggest motive for introducing this bill seems to be the combination of the oligarchs’ past media and political influence. The official designation of individuals as “oligarchs” would be up to – again – the NSDC. One source estimated there would be 13 people who fit the criteria. Anyone who did would go on an official register. They would have to make e-declarations of their assets and would be banned from participation in future privatisations, which would be reserved for those with an “impeccable business reputation” (disqualifying anyone facing international sanctions). Designated oligarchs would be banned from financing political parties; and, in any contact with politicians and officials, they would have to declare their status and their interlocutors would have to declare the contact.

Parallel measures include tax changes designed to raise money from specific oligarchs: increased rents on iron ore mining and an excise tax on electricity produced from renewal energy sources. There was discussion of a potential future tax amnesty, which it was hoped – optimistically – would legalise $20 billion of shadow capital and raise $1 billion extra.

The bottom line is that the bill would transfer power to the NSDC. The four criteria for defining who is an oligarch are inexact, leaving wide scope for politicised decisions. It remains to be seen whether there will be a genuinely broad crusade, the targeting of particular individuals, or the clearout of Zelensky’s opponents before the next elections.

Is Zelensky really leading a general anti-oligarch campaign?

In Zelensky’s Ukraine, the good and the bad, reform and reaction, all coexist. This multiverse is a suitable reflection of Ukraine’s post-modern comedian-president. There is as yet no general, credible anti-oligarch campaign. This year’s moves against Medvedchuk can be explained by national security expediency and by the standing of Zelensky’s party in the opinion polls. The ambiguous moves against Kolomoisky can be explained by the urgent need to build bridges with Washington. At the same time, the threat from Russia forced Ukraine to seek help from the US, which increased Washington’s leverage on reform.

Critics of Zelensky, particularly those from the opposition European Solidarity party, contend that the president is motivated by nothing but opinion polls. Worse, they claim, he is acting entirely as was predicted in 2019: as an actor-president obsessed with, and only competent at, managing his media image. According to political analyst and opposition MP Rostyslav Pavlenko, “it seems that Zelensky and his entourage are running a television show, which has its episodes and series. If they see their ratings go down, they invent a new plot, new characters, new heroes and enemies. If that helps the political situation, all the better; but that’s not the main reason.” On the anti-oligarch campaign specifically, Pavlenko argues that: “They are imitating the fight with oligarchs rather than having a real fight”.[12]

Over the last year, Servant of the People became squeezed between the Opposition Platform and Poroshenko’s European Solidarity party. But, with the advance of the fightback, the rise of the Opposition Platform was halted, and Servant of the People won back some ‘patriotic’ and pro-EU votes from European Solidarity. By early March, Servant of the People was back on top in the polls, on more than 20 per cent of the vote. The attacks on Medvedchuk helped Servant of the People win a crucial by-election in the traditionally ‘patriotic’ area of Ivano-Frankivsk, in west Ukraine, in April 2021.

Other observers think the president is still finding his feet, and learning the hard way how to balance domestic and international pressures. Political analyst Oleksiy Haran says that “what’s happening with Zelensky right now is what we said needed to happen in 2019. His moderate rhetoric is OK. But he’s become more assertive with Russia. He relies more on Ukrainian patriots. Zelensky has taken steps, but there are more to take.” The fightback really could mark the start of a new fourth – reformist – phase in Zelensky’s tenure. But, with every step forward, there will likely still be steps back. “We don’t know how stable this trend is. We haven’t seen too many results. And there are people around him like Yermak who have been prepared to deal with Russia’s proxies in the Donbas.”[13]

Some parts of the Ukrainian multiverse contain opportunities for progress. There have been significant reforms in Ukraine since the revolution in 2014; but it has always been a difficult process. According to one EU official in Kyiv, “reform in Ukraine is a street battle; you have to bring a baseball bat. But nothing is impossible if you are tough enough.”[14] Many recent reforms were initiated under Poroshenko or when Honcharuk was Zelensky’s prime minister, which meant that the reform processes were locked in. Crucially, they were also supported by international players such as the US and the EU, albeit severely undermined by the Trump administration. Such locking-in of reform through the strength of international support is an example to pursue in the future. And circumstance and the security situation may be forcing Zelensky to go further. He is becoming more realistic about the threat from Russia and the oligarchs’ cynical bandwagoning with Russian propaganda. With the right pressure from the international community, elements of a reform agenda could be back on track.

That said, the politicisation and informal use of the NSDC is problematic. The charge of treason levelled against Medvedchuk does not fit neatly into the supposed anti-oligarch drive but smacks of searching for any way in which to act against him. Sanctions risk becoming the default response and a general foreign and domestic policy tool. In January 2021, the NSDC sanctioned Chinese company Skyrizon to prevent it from taking over aeroplane manufacturer Motor Sich. In February, Ukraine imposed sanctions on Nicaragua after it opened an honorary consulate in Crimea. The builders of the Kerch bridge have been sanctioned, as have French MEPs who visited Crimea and ten “traitor generals” charged with failing to prevent the annexation of Crimea. In March, investigations were announced against members of parliament who ratified the Kharkiv Accords with Russia in 2010, which extended Russia’s lease on the Black Sea fleet at Sevastopol and allowed it to ramp up covert operations in Crimea.

Russia looms as large as ever. Many of Ukraine’s recent moves have been driven by domestic security concerns, but there is a risk that Russia will react to them with hostility. Indeed, on 14 May, Putin claimed at a meeting of his own NSDC that Ukraine was becoming the “anti-Russia”, and that the “cleansing” of political space in Ukraine – that is, moves against Medvedchuk – was “news requiring our special attention from a security point of view”. He added: “we should respond to this given the threats being created for us in a timely and appropriate manner”. The situation creates a moral obligation for the West to support Ukraine in so far as it has been pushing for such reforms.

It is, therefore, no coincidence that Ukraine has lately increased its rhetoric about its NATO aspirations, and called for the US, the UK, and Canada to join the Normandy format. That said, Ukraine’s government has used the war in the east on many occasions as an excuse to delay or water down reform. Having reached out for security assurances in spring 2021, the it has been forced to at least talk the talk of renewed reform.

To ensure this happens, it is important to understand that Zelensky’s inner circle are essentially businessmen. They are highly transactional; they understand hardcore conditionality if they want something in return, which explains improved relations with the US rather than the IMF. But they have less understanding of the nuances of diplomacy or the idea that IMF support is as much about investor confidence and international support as it is about direct financial backing. Biden’s actions so far vindicate the approach of adopting tougher conditionality and greater clarity about what this support means. Diplobabble does not work: the EU should, therefore, follow the US approach and be clear and tough with Kyiv in private while offering more support in public. The EU should adopt stronger conditionality and red lines, and should take a less bureaucratic approach. The Biden administration provides an opportunity for coordinated support that both the EU and the US should capitalise on.

Recommendations

The EU, the US, and the UK need to send clear, coordinated messages condemning selective justice and informal and ad hoc administration in Ukraine. Sanctions are a blunt instrument that should not become a general foreign policy tool. And there is a risk that Zelensky’s tendency to exert influence informally will lead to reforms that are shallow rather than thoroughgoing and long-lasting.

However, the EU, the US, and the UK also need to be consistent in offering security support. The Biden administration’s on-off deployment of two warships to the Black Sea in April undermined the messaging to Russia of US support for Ukrainian sovereignty. Increased Russian pressure in the Sea of Azov soon followed. Similar changeable messaging from Washington about Nord Stream 2 has the same effect.

More reliable security assistance for Ukraine must become an important part of support for the country generally and its reformists in particular. On the relationship with NATO, a row over giving Ukraine a MAP would be damaging for all. But there is scope for enhanced security cooperation short of a MAP. The EU should: increase its engagement on (and physically in) east Ukraine; provide more backing for reform of the judicial and security sectors; and offer more support to counter hybrid threats and disinformation. A proposed EU Advisory Mission office in Severodonetsk in Donbas, in addition to the new field office in Mariupol, is a good idea. The OSCE Special Monitoring Mission could be given more teeth.

Ukraine also needs help with its coronavirus vaccination programme. At the current pace, vulnerable groups are unlikely to be vaccinated at all in 2021. Both the EU and the US can step up by sending more vaccines to Ukraine. (Denmark has offered 500,000 doses.) And Ukraine would like to see the full resumption of freedom of movement to the Schengen zone as soon as possible. This gives the EU additional leverage – which it should make the most use of, coordinating closely with Washington.

About the author

Andrew Wilson is a professor of Ukrainian studies at UCL School of Slavonic and East European Studies. A new edition of his book Belarus: The Last European Dictatorship will be published next year, covering recent events.

[1] ECFR interview with Petro Burkovsky, 6 April 2021.

[2] ECFR interview with senior EU official based in Kyiv, 8 April 2021.

[3] ECFR interview with Oleksiy Haran, 6 April 2021.

[4] ECFR interviews with Ukrainian experts, April 2021.

[5] ECFR interview with Petro Burkovsky, 6 April 2021.

[6] ECFR interview with senior EU official from Kyiv, 8 April 2021.

[7] ECFR interviews with Ukrainian experts, April 2021.

[8] ECFR interview with senior EU official from Kyiv, 8 April 2021.

[9] ECFR interview with senior EU official from Kyiv, 8 April 2021.

[10] ECFR interview with Petro Burkovsky, 6 April 2021.

[11] ECFR interview with senior EU official from Kyiv, 8 April 2021.

[12] ECFR interview with Rostyslav Pavlenko, 9 April 2021.

[13] ECFR interview with Oleksiy Haran, 6 April 2021.

[14] ECFR interview with senior EU official from Kyiv, 8 April 2021.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.