Talking to the Houthis: How Europeans can promote peace in Yemen

Summary

- Early Houthi promises to Yemenis of fairer and more transparent government have come to nothing, and the group exerts a rule of brutal suppression.

- The Houthis now govern over most of Yemen’s population and should be included in efforts to end the conflict and restore peace to the country.

- The Houthis seek international recognition, face growing internal challenges, and may no longer want to extend their control over southern Yemen. This provides some negotiating space.

- While the Houthis benefit from Iranian support, they are driven by their own interests and will wage war regardless of Tehran’s position.

- European states should now increase conditional engagement with the Houthis, looking to widen political and humanitarian space on the ground, while pushing all sides to the negotiating table.

Introduction

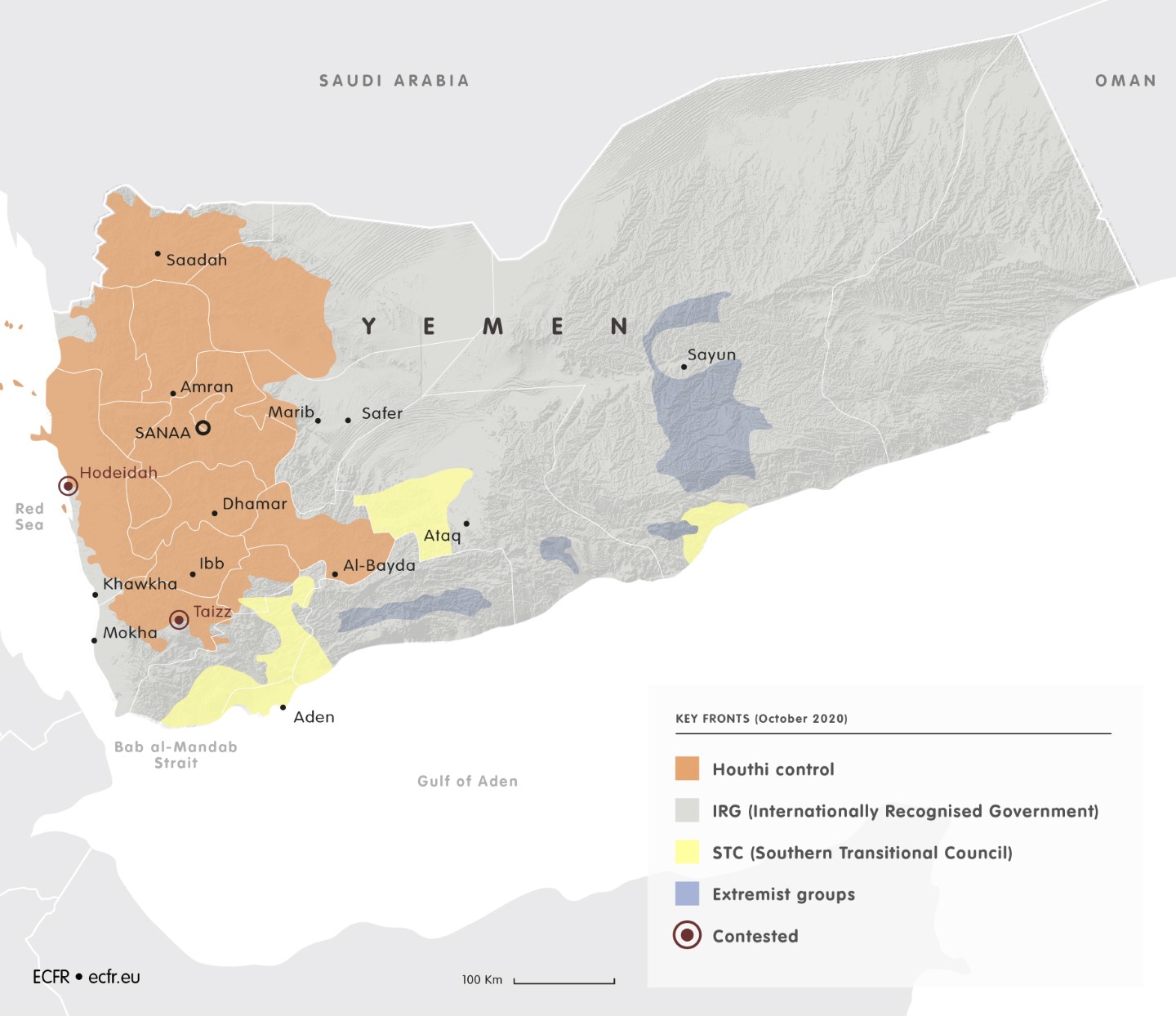

The Houthi movement rose from a highly localised position in the far north of Yemen two decades ago to today fully controlling one-third of the country’s territory, in which two-thirds of the Yemeni population lives. In 2020 it has again been on the offensive. With limited support from Iran, the Houthis have held at bay a Saudi-led coalition of ten countries supported by the United States, the United Kingdom, and EU member states – a coalition that is armed with the most sophisticated and expensive military technology in the world.

For the European Union to assess developments in Yemen and create a strategy to restore some kind of stability and peace to the country, it is essential to understand different aspects of the Houthi movement: its ideological development, the mechanisms it uses to control the population, and the sources of its financial resilience. These are all relevant to explaining its successful resistance to the Saudi-led coalition. Moreover, an understanding of the internal dynamics of the Houthi movement can give European policymakers insight into better ways of dealing with the group.

This paper seeks to explain how and why the Houthis – or “Ansar Allah”, as they call themselves – have achieved their current dominance of the Yemeni political and military landscape. It examines what this means for the future of the country and ending the current war. The paper paints a worrying picture of Houthi control and governance, but nonetheless recommends that the EU and its member states recognise the need to more proactively engage the Houthi movement if political progress is to be made. This engagement should include pushing back against current attempts by the US and Saudi Arabia to designate the Houthis a terrorist organisation, which would only serve to cement the position of hardline forces within the group. European actors should better leverage this engagement to achieve behavioural change on the part of the Houthis, with an immediate focus on the humanitarian space. This would represent a necessary first step towards improving immediate conditions on the ground and strengthening the prospects for a more inclusive political track that involves all parties to the current conflict.

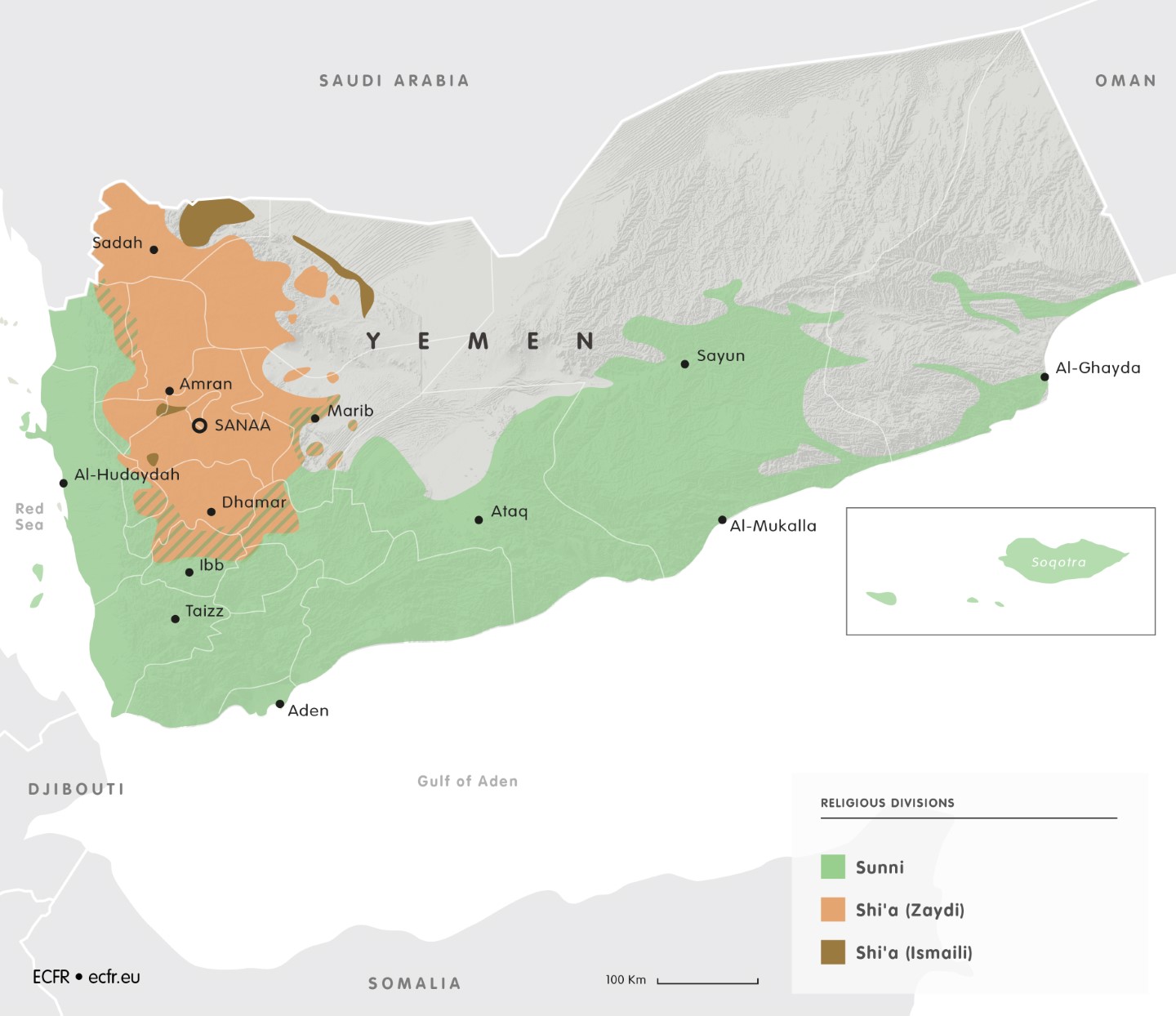

The development of Ansar Allah

The Houthi movement emerged from Zaydi Shia revivalist group Believing Youth, led by Hussein al-Houthi, in the 1990s to become an armed political movement in the far north of Yemen. Zaydis are “Fiver” Shi’ites, in contrast with the Iranian “Twelvers”. In Yemen, this means that they have historically had few doctrinal differences with the Shafi Sunnis who form the majority of Yemen’s population. Zaydis live in a deep pocket of highlands that starts at the Saudi border, and are surrounded by Shafis, who live along the coast, south of Yarim, and in the arid eastern regions.

The Houthi movement is led by the Houthi family, who are sada – descendants of the Prophet; “Hashemites” and “Ashraf” are alternative terms for this social stratum. The Houthi movement emerged in reaction to the rise of imported Salafism in the group’s heartland around Saada governorate, in north-western Yemen, as well as a perception of neglect and lack of development investment in its region by the central government. In the same period, a Zaydi political party, Hizb al-Haq was created. Collectively, Believing Youth and Hizb al-Haq saw themselves as a bulwark against Islah, a major Yemeni political party combining Sunni Muslim Brotherhood-type Islamists and northern Zaydi tribesmen. Between 2004 and 2010, a series of six increasingly violent and destructive military confrontations took place between the Houthi movement and the regime of then-president Ali Abdullah Saleh. His main military force in the region was led by General Ali Mohsen al Ahmar, who today is vice-president of the internationally recognised government (IRG) of the current president, Abdurabbuh Mansur Hadi.

The Saada conflict ended with the momentous uprisings of 2011, when the Houthis joined the popular movement against the Saleh regime. The 2011 uprisings throughout the Middle East generally called for a more democratic and equitable polity; in Yemen, protesters sought inclusion in the political realm of formal and informal opposition to Saleh. In March 2011, the “Friday of Dignity” massacre – in which 50 demonstrators were killed – took place in Yemen’s capital, Sanaa. At this point, even Ahmar and other former allies of Saleh joined the protest movement. During these chaotic times, a political vacuum emerged in Saada. Abdulmalik al-Houthi – who took over leadership of the movement after his brother, Hussein al-Houthi, was killed in 2006 – appointed his own governor, and the province became the first part of Yemen to formally shake off central government control.

The Houthis used their participation in the anti-Saleh movement to spread their political and ideological beliefs, as well as to gain experience in civil society activism. They chose to stay out of the transitional government established by the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) Agreement of November 2011 under Hadi. But, in 2013 and 2014, they participated in the National Dialogue Conference (NDC), one of whose nine working groups was devoted to the “Saada issue” – a euphemism for the Houthi movement. In this period, the group simultaneously took successful military action to expand its territorial control into parts of Hajjah, Jawf, and Amran governorates, and started to exercise its administrative skills in Saada (which, by then, was fully under its control).

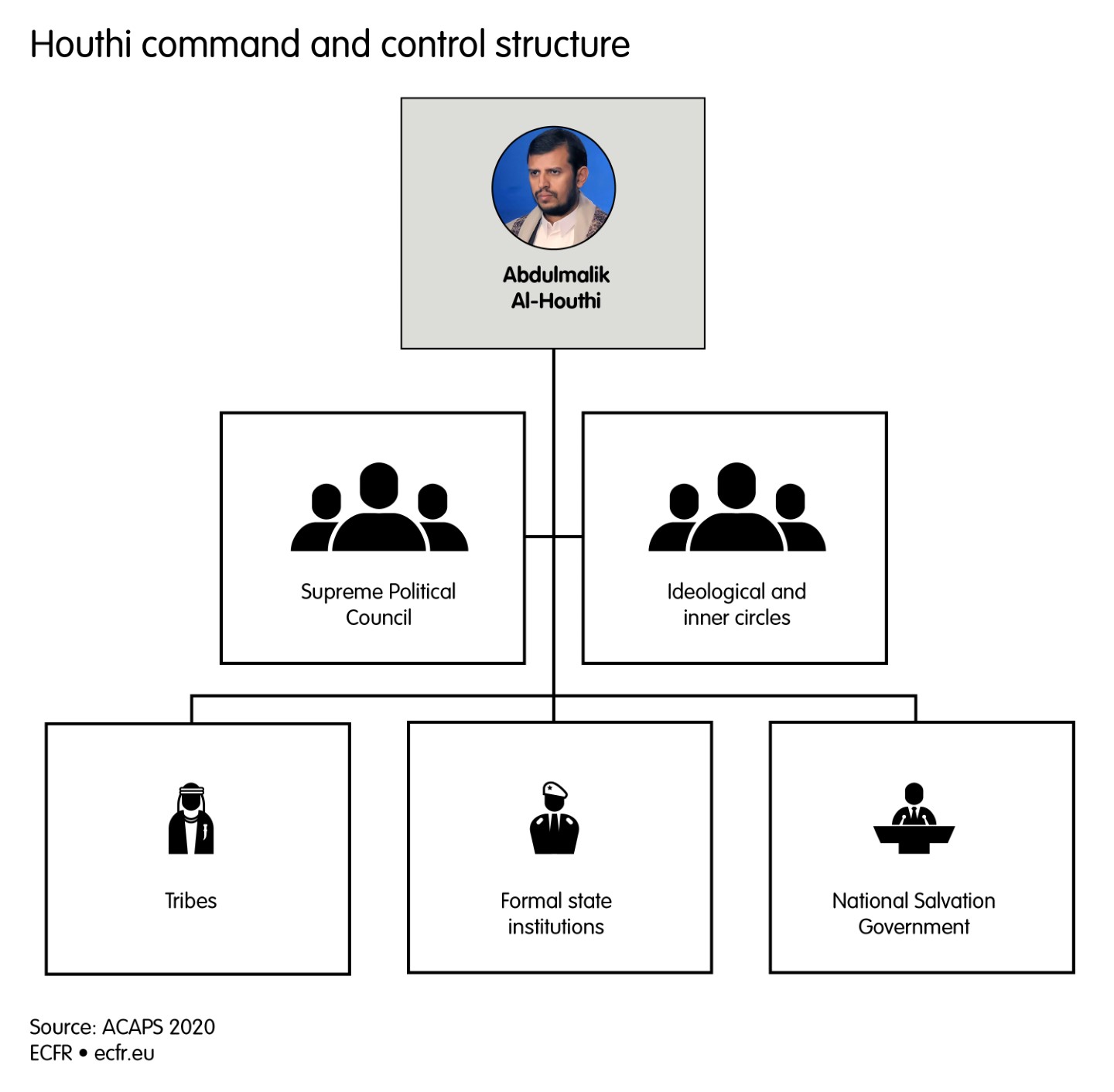

Supreme Revolutionary Committee

The Supreme Revolutionary Committee (SRC) was established on 6 February 2015 as part of the ‘Constitutional Decree’ announced by the Houthis when they formally took over Sanaa. It is responsible for leading the revolution centrally and through local Revolutionary Committees in governorates and districts. Its leader is Mohammed Ali al-Houthi, who is now a member of the Supreme Political Council (SPC). It continues to operate in 2020. It is an exclusively Houthi organisation and does not claim to include other political groupings. Its supervisors are members of Revolutionary Committees.

Supreme Political Council

Established in July 2016, the SPC was officially designed to replace the SRC but, in practice, they operate alongside each other. It is a more inclusive institution: five of its members are from the GPC, and five from the Houthi movement. Its head is officially the president of the republic for Houthi-controlled areas. Its leadership was initially set to rotate between the Houthis and the GPC, but has remained with the Houthis throughout. Its first president, Saleh al-Samad was killed in a coalition airstrike on 19 April 2018. He was replaced by Mahdi al-Mashat. Mohammed Ali al-Houthi, who has a double role as a member of the SPC and the head of the SRC, is currently the most vocal representative of the Houthis.

Government of National Salvation

Established in October 2016 by decree of the SPC, the government has, since then been headed by the prime minister, Abdul Aziz bin Habtoor (of the GPC), and includes both Houthi and GPC members. While it may have a considerable local administrative role, its political role is subservient to the SPC and SRC, and it has a limited international presence.

Both the Houthis and Saleh opposed the post-NDC, six-region federal arrangement planned by the transitional regime, fearing that this would cut off their access to the Red Sea in the west and to the oil-rich governorate of Marib in the east. Their shared opposition to the transitional regime created a de facto alliance between the Houthis and Saleh – who, at that time, still had a considerable hold on Yemen’s military and security forces. This tacit strategic alliance enabled the Houthis to expand their power southwards through military force in 2014, reaching Sanaa in summer that year. The Hadi regime effectively handed the capital to the Houthis on a platter by abruptly removing fuel subsidies, leading to popular demonstrations against the government. The Saleh-Houthi alliance capitalised on the removal of the subsidies, which appeared to support the Houthis’ claim to represent a transparent and non-corrupt alternative to Hadi. By February 2015, after Hadi and his officials resigned and were placed under house arrest, the Houthis promulgated a constitutional declaration that replaced the government with the SRC, which had branches throughout Houthi-controlled territory.

In 2016 the Houthis replaced this body with the SPC, followed a few months later by the National Salvation Government. Both bodies reflected the dominance of the Houthis in their alliance with Saleh’s party, the General People’s Congress (GPC). The formation of the National Salvation Government was a major step in turning the Houthis from a primarily military organisation into one managing political and administrative institutions.

In December 2017 the Houthis assassinated Saleh, leaving only one section of the GPC playing a (minor) role in Sanaa. Overall, the GPC has lost its collective voice, although it still retains considerable representation in parliament, where debates are broadcast live, and MPs are openly critical of certain policies. Following Saleh’s death, many of his former military men were forced to resign from long-held positions and stay away from politics in general, creating resentment within their supporters’ ranks. The military apparatus is now dominated by Houthi figures, many of whom lack formal military training, although they are battle-hardened. GPC figures in Sanaa publicly pronounce their freedom to disagree with the Houthis but, in reality, the group tolerates no dissent.

Houthi rule

The area under Houthi control has changed little in the past five years. In March 2015, the Houthi-Saleh alliance captured Aden and Hadi, who had previously escaped Sanaa and established Aden as the country’s temporary capital, called on Saudi Arabia and the GCC to intervene and protect his regime. This led to the launch of the Saudi-led offensive “Decisive Storm”, which began in late March that year as Hadi took refuge in Riyadh. For Saudi Arabia, the Houthis’ control was an unacceptable threat given their links to Iran. Saudi Arabia was also opposed to the Houthis’ religious proselytising, which challenges the Al Saud rule over Islam’s holiest places; their promotion of sada as the only legitimate rulers; and the threat to the Hadi regime itself. The new minister of defence at the time, Mohammed bin Salman, also appeared confident that the coalition forces would easily defeat the Houthis.

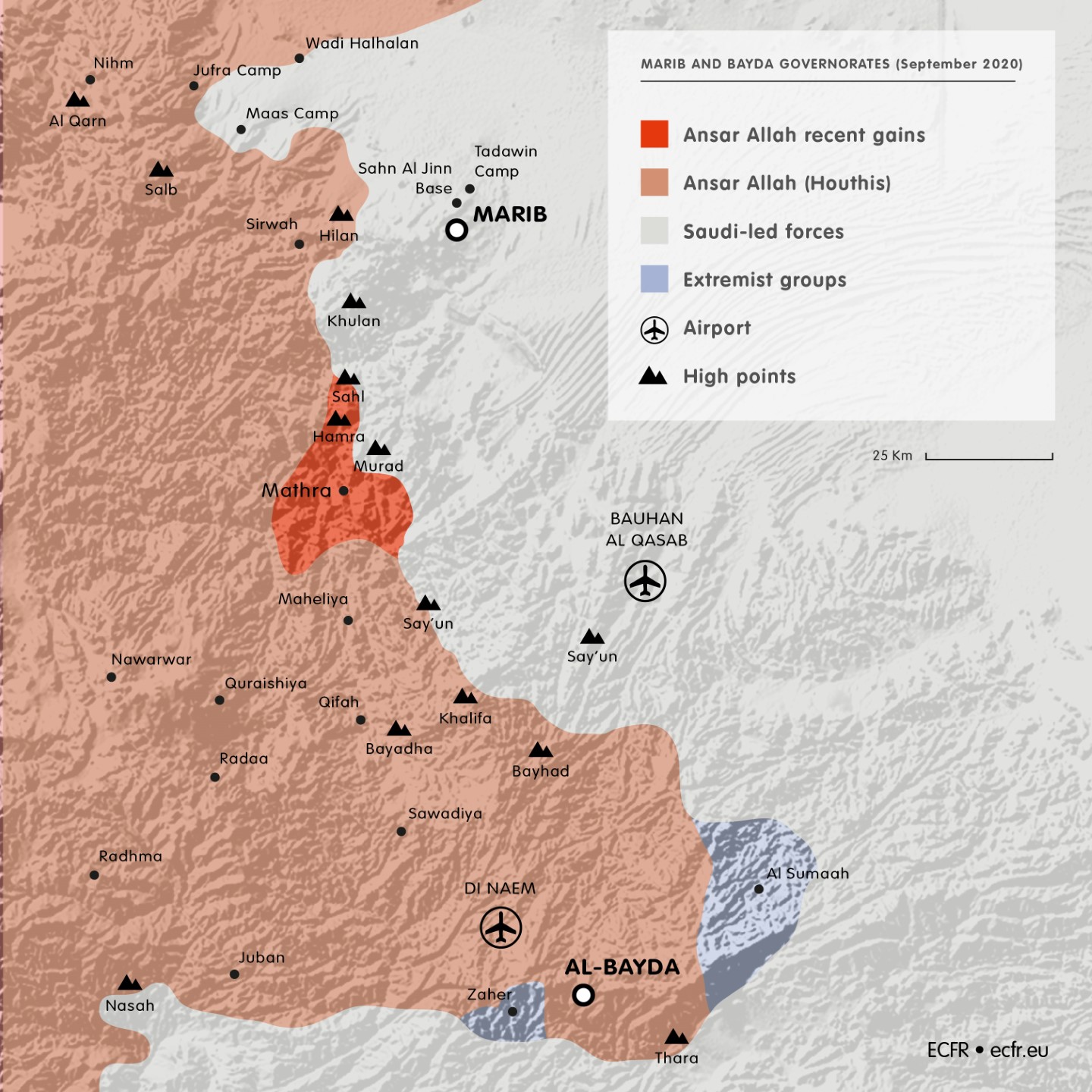

By mid-2015, the Houthis had gained full control of governorates further south and west through a series of negotiated takeovers and military campaigns, including those in Hodeidah and the entire Red Sea coast stretching to the Bab al-Mandab, as well as Dhamar, Ibb, and Al Bayda, in the centre of the country. The group lost Aden to southern forces backed by the Saudi-led coalition in July 2015, and never gained control of other southern governorates. Taiz has remained a complex front line since that period. Militarily, in 2017, the Houthis lost southern Tihama – between the Bab al Mandab and the outskirts of Hodeidah city – where another front remains active to date.

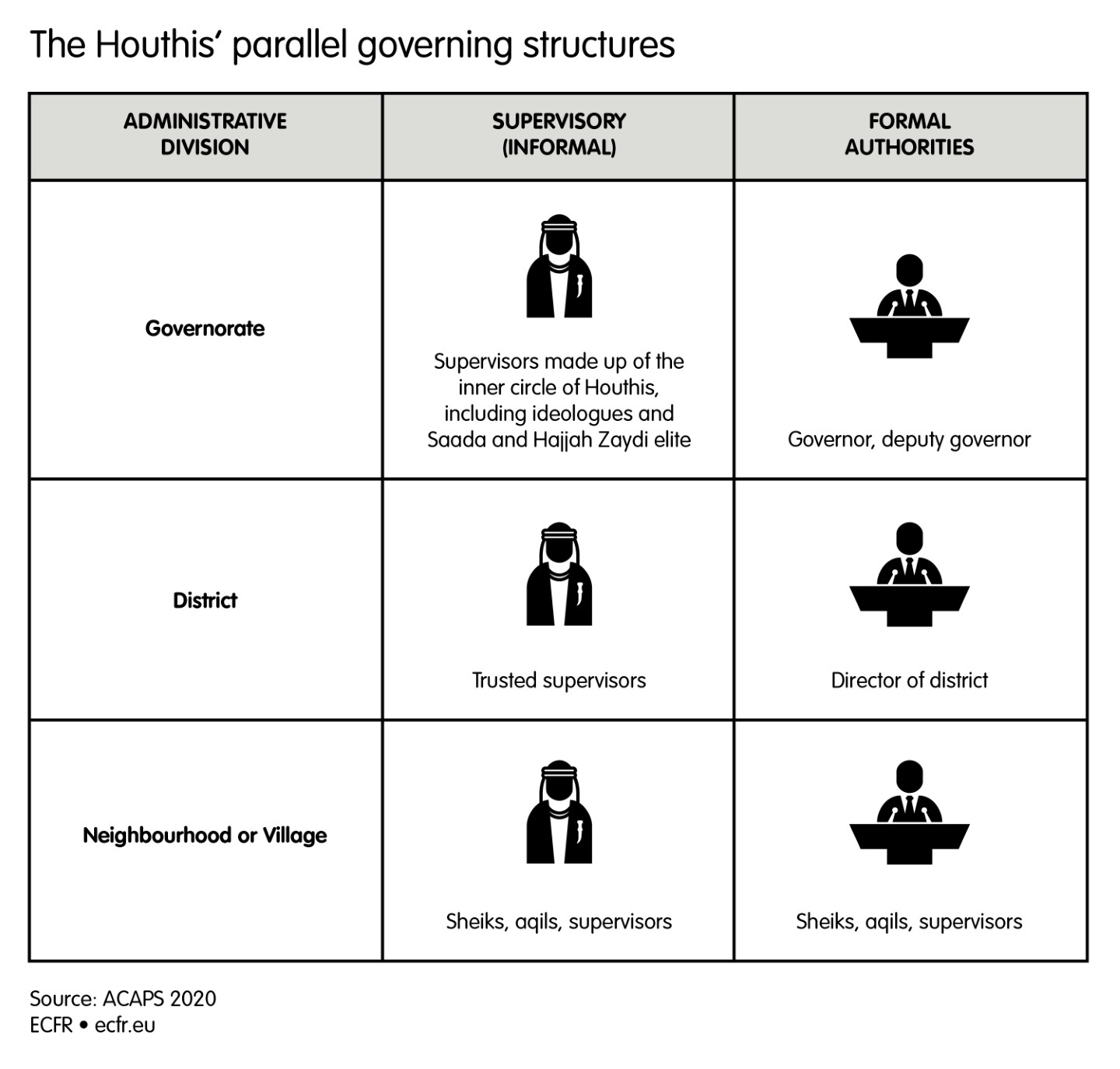

Saudi and Emirati underestimation of the Houthis’ strength quickly proved costly to the coalition campaign. But the Houthis have additional advantages that facilitated their success. First and foremost is their control of the country’s capital, which automatically brought Yemen’s highly centralised administrative structure under their control, including the experienced personnel of ministries in Sanaa and at the governorate level. Rather than following the disastrous approach of clearing out sitting officials – as the US did following the 2003 invasion of Iraq – the Houthis left incumbents in place but installed a layer of ‘supervisors’ to direct their work. These supervisors range from Houthi elites from Hajjah and Saada to young, unqualified men (the Houthis do not believe in giving women political or other authority). These Houthi loyalists ensure that the movement’s decisions are implemented, that jobs go to their supporters, and that financial advantages primarily benefit the Houthi movement. As increasing numbers of officials are Houthi appointees, the supervisor system is gradually becoming obsolete, though this may cause friction within the movement if and when supervisors lose their jobs.

The Houthis’ original promise of transparent governance is now long dispelled for the millions living under their rule. The Houthis interfere in most businesses, mainly to extort taxes and customs duties under multiple pretexts, including the “war effort”. In June 2020 they imposed a 20 per cent zakat tax on all economic activity, reflecting their urgent need for income provoked by the ongoing conflict, their international isolation due to the Saudi-led siege, and a collapse in remittances cause by the covid-19 outbreak. The Houthis also now monopolise the telecommunications sector: Yemen Mobile controls the operations of most telecommunication companies in the country, including those operating in the areas under the authority of the IRG and other groups (the exception is Sabafon, which allegedly broke free from Sanaa and moved its headquarters to Aden in September 2020). The IRG has no choice but to tolerate this situation if services are to continue throughout the country, even though this gives the Houthis a stark advantage in surveillance.

The Houthis have been similarly determined in maximising their control over international humanitarian financial and material aid, as most Yemenis in need of humanitarian assistance reside in areas under Houthi control. They do this to strengthen their hold over the population and to ensure a steady income stream for themselves. The Houthis’ systemic interference in relief operations provoked a clash with the UN humanitarian community that led to a dramatic drop in overall aid in 2020, as funders refused to continue indirectly financing the Houthi movement.

The group also exerts social control, such as by closing enterprises they view as controversial, including coffee shops, which allow men and women to socialise together. The Houthis spread their beliefs through religious propaganda, such as Abdulmalik al-Houthi’s “Quranic March”. This manifesto covers the cultural, political, and religious tenets of his movement; it is grounded in the teachings of Hussein al-Houthi, who began promoting his beliefs in 2004, during the first Saada wars. The document speaks of achieving a harmonious society with strong leadership, based on a strict interpretation of the Quran. During the transitional period of 2012-2014, Yemenis experienced expanded press freedoms and increased public participation – liberties that the Houthis exploited and then shut down for the purposes of political and religious messaging (which has assumed an increasingly anti-Semitic and anti-Zionist tone). Meanwhile, the group targets young people through its control over Yemen’s education system, altering curriculums to normalise Yemen’s war environment, and indoctrinating a generation of young Yemenis to view the Houthi movement not just uncritically but as fundamentally righteous. In 2014 and 2015, the Houthis created a committee that revised the primary and secondary school curriculums to fit their ideology. The Houthis heavily promote jihad in the areas they control, where indoctrinated locals believe that events in Yemen are entirely the result of a Zionist-American conspiracy.[1] Ultimately, the Houthis have largely monopolised the Zaydi school in Yemen and eroded its once moderate standing.

More than anything, however, the Houthis exert control through highly effective repression of the population. In September 2019, the Houthis replaced Yemen’s intelligence bodies, the National Security and Political Security agencies, with the new and efficient Security and Intelligence Service. They established an all-female force, the zainabiyat, to crack down on female dissidents. The Houthis also endowed traditional community neighbourhood leaders known as aqil with greater privileges and authority, such as the rationing of gas for locals. These figures have become important tools for the Houthis in recruiting fighters.

On the ground, dissent leads to arrest and imprisonment, fabricated legal charges, and harsh sentences. The Houthis’ control of various technological services and mechanisms allows them to keep track of social media and other cyber activities, while individuals such as supervisors are also active in watching people and reporting dissent. Free speech is not among their policies: journalists are a particular target, suffering extra-legal indefinite detention and abuse, as well as severe punishments in court, including death sentences. The Houthis publicly label anyone who disagrees with them as either a “Saudi conspirator”, a “terrorist”, or an “Islahi”. The harsh Houthi behaviour also extends to the treatment of religious minorities. The few remaining Bahais in Yemen faced years of attacks and intense persecution from the Houthis. Arrested and sentenced to death, they were finally expelled from the country in July 2020 after considerable international pressure.

The Houthis might claim to tolerate dissent but, in reality, they systematically weaken the powers of any tribe, group, or political party that does not follow orders. The group has the weapons, the resources, and a sophisticated propaganda apparatus capable of silencing any voice they perceive as threatening. Houthi governance methods are unlikely to change while the war continues, as it enables them to label any opposition to their policies as collusion with the enemy.

The Houthis’ domestic goals

Religious and political ambitions

Broadly speaking, the Houthis promote a neo-Zaydi ideology that is mostly obscure and ill defined, yet is increasingly political and militaristic. Perhaps its only clear expression is the belief that the sada have the right and authority to rule on the exclusive basis of their ancestry. This is a belief mostly manifested by the systematic appointment of members of that social group to vacant senior military and government positions. More general Ansar Allah beliefs include the duty to rise up against unjust rulers (namely, the IRG) and the use of force to achieve political power. The “Quranic March” is critical of democracy and calls for the creation of a theocratic state.

Some Houthi rhetoric expresses a desire for a modern, republican Yemen. Much of this is reflected in the group’s National Vision for the Modern Yemeni State, published in 2019. This document says nothing about religious rule or the role of the sada, but instead presents a vision that could well be secular and fully representative of the interests of the population. However, the group’s recent imposition of taxes, gender segregation, and preference for Hashemites in leadership positions reflect its ultimate goal of resurrecting Yemen’s historical Zaydi socio-political dominance. Despite firm denials from the movement’s SPC members, the Hashemite legacy is clearly a primary source of inspiration to the Houthis. However, while the Houthis themselves are animated by this objective, they are clever enough to realise that Hashemite rule does not appeal to the majority of Yemenis. The Houthis have, therefore, promoted the almost secular nature of their National Vision for the Modern Yemeni State document, while also cloaking their ambitions to establish an imamate by overtly emulating the Iranian model. In this way, the group takes Abdulmalik al-Houthi as its spiritual and main authority, while the SPC carries out political activity under the guise of republicanism.

Years of wartime governance have cemented the group’s hardline position. While the Houthis are not homogeneous, the group has become increasingly dominated by hardliners who are more resistant to accommodating dissent and more willing to pursue violence to achieve their political ambitions. Whereas the more intellectual members of the group were its face during the National Dialogue Phase in 2013 and 2014, these members were increasingly sidelined as the war progressed. Indeed, as the Houthis tightened their grip on the north between 2013 and 2015, some of their more tolerant advocates were killed in a string of assassinations, possibly conducted by other Houthis. The trajectory of the Houthi political wing can also be understood by examining the case of Samad, who was head of the SPC. Government officials in Sanaa noted that Samad requested Houthi slogans be removed from state institutions and that he justified his inclusive political effort by criticising the group’s monopolisation of power. While Samad tried to work as a head of state and attempted to pursue a more political path, he was stymied by considerable opposition from influential Houthis. Samad was killed by the Saudi-led coalition in April 2018. He was replaced by Mashat.

Typically, intra-Houthi disputes are now about controlling institutions, sharing financial and land interests, and struggling for power generally – rather than the future of the country and the Houthi vision for the state. Elite-level disputes tend to erupt over the distribution of revenue on the black market for oil, positions within the military, telecoms income, and other targets of embezzlement. For example, Abdulkarim Amir al-Din al-Houthi (the uncle of Abdulmalik, the current minister of the interior and the de facto ruler of Sanaa) and Mashat reportedly became embroiled a disagreement over the former’s unilateral appointment of 44 new police directors in April 2020. In general, the leadership prizes kin and loyalty above competence, and maintains the status quo by fostering a climate of intolerance of even the slightest form of dissent. The example of Saleh Habra, who represented the Houthis during the NDC and served in the SPC, also demonstrates how the group deals with internal dissent: in early July 2020, Habra warned on Twitter that the group would face repercussions unless its leadership held its members accountable for corruption within its ranks and stopped imposing exclusionary and oppressive policies. Following this statement, Habra disappeared from the media, signalling that the group has little tolerance for internal dissent even from high-ranking members. He has not been seen in public since October.

The marginalisation of the Houthis’ more tolerant members is both a cause and an effect of the group’s increasing militarisation; the Houthis’ increasing heavy-handedness and violence no doubt caused its more tolerant members to fall away, while its more strident, less ideologically nuanced followers were more likely to rise to the top amid the harsh wartime environment. At the same time, the marginalisation of the group’s moderate members has reduced their influence on Houthi ideology, strategy, and discourse, which increasingly leans away from peace and towards a forever war. As long as hardliners achieve military success, or until the conflict in Yemen ceases, the hardliners will remain in the ascendant. Given the events of the past two decades, it is not entirely surprising that Houthi hardliners remain strong; all any Houthi has to do is look at where they were in 2004 and compare it with their current position.

Territorial ambitions

Officially, the Houthis call for a united Yemen in which they hope to have considerable, if not exclusive, power. However, they have shown decreasing interest in Aden and neighbouring governorates since they failed in their attempt to take over these areas in 2015. The positioning of their troops suggests that the Houthis have limited interest in expanding into southern Yemen. Despite the fact that some Houthi hardliners maintain a maximalist position and support a forever war, it is not inconceivable that the Houthis could eventually find some form of accommodation with southern separatists.

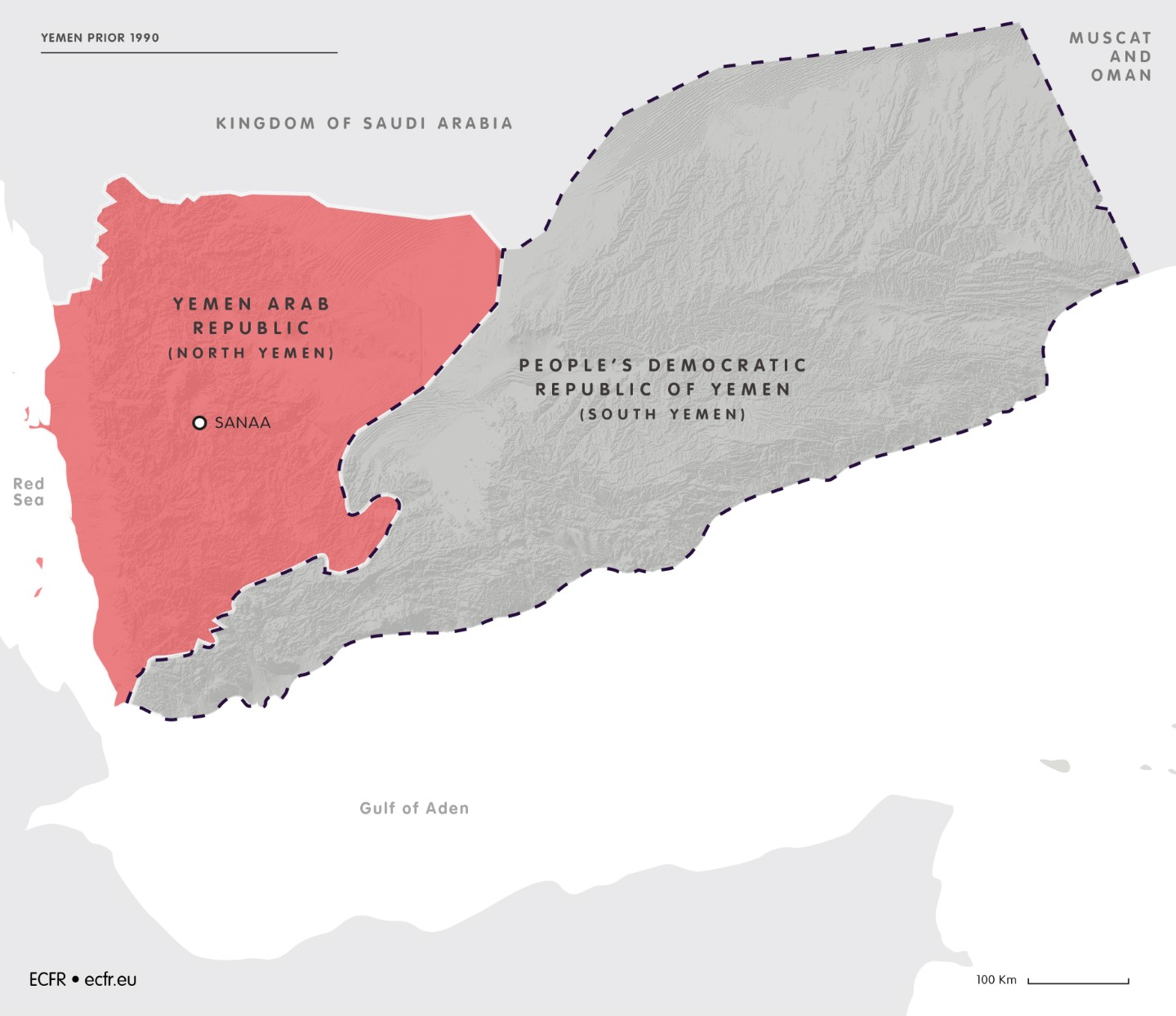

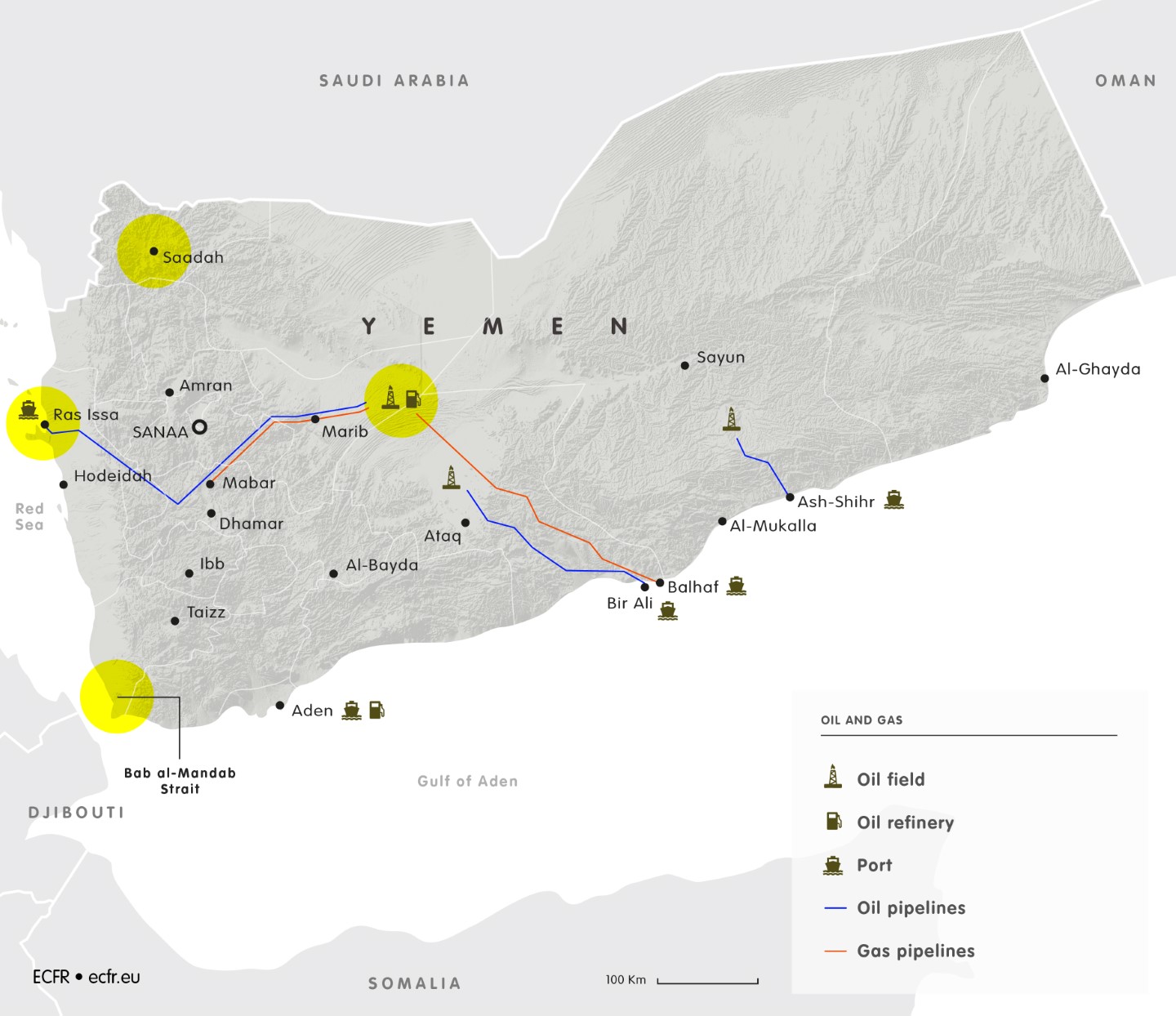

Their geographic ambition is now focused on controlling Marib, Hodeidah, and Taiz – to at least gain the symbolism of having the same territory as the former Yemen Arab Republic, which dissolved with Yemeni unification in 1990. Having pushed Islah entirely out of northern territories, the Houthis are now campaigning to seize Marib city, which is under IRG control, and whose population has grown exponentially – with about one million internally displaced persons and others creating a total population of about two million (before the war, Marib governorate was home to fewer than 300,000 people). The Houthis’ potential takeover of Marib could deal a fatal blow to the IRG, affecting its strongest element, the Islah party, as well as crippling Saudi Arabia’s ongoing Yemen campaign. The Houthis are making strenuous efforts and committing significant resources in their push for Marib, reflecting their recognition of the political and economic prize the city represents as both the base of the IRG and a major source of oil and gas income. Taking it would allow the Houthis to regain financial losses stemming from cutbacks in humanitarian aid, oil revenue, and the economic decline compounded by the covid-19 pandemic.

The Marib governorate historically persisted as one of the few northern areas that rejected rule by the traditional northern elite, both during the imamate until Yemen’s revolution in 1962, and under Saleh. The outcome of the Houthis’ attempt to capture Marib will entirely depend on how much the coalition supports the IRG. It is likely that the Saudis will continue to fight hard for Marib.

Hodeidah, meanwhile, is important to the Houthis for two main reasons: firstly, it provides an economic and humanitarian lifeline; secondly, the city is completely Shafi, and the Houthis need to appear tolerant of communities outside their sect in order to avoid international accusations of sectarianism. But, in Taiz, the Houthis’ objective has been to bleed the IRG and all forms of anti-Houthi resistance. To this end they have besieged the city since the beginning of the conflict. This has been an effective approach: the Houthis control access to the city, while mistreating residents at will. In the meantime, pro-IRG forces fight among themselves, further discrediting the ability of the legitimate government to demonstrate political leadership or mount a military resistance. After the conflict ends, areas such as Taiz will pose a significant challenge to any transitional period, because the Houthis will struggle to govern an embittered and conflict-scarred local population.

For the Houthis, a state of war has been their reality for so long that it represents normality and is even encouraged. The Houthi family and leadership have seen decades of conflict and view martyrdom as a blessing. The Houthis’ capacity for resistance has proved perhaps the most challenging non-military aspect of the fight against them. The Houthis are capable of recruiting a seemingly endless number of fighters, including children, by drawing on popular support for their war efforts and by working with sheikhs and other neighbourhood leaders. Ultimately, this revolutionary mentality and recruitment drive is what fuels the group’s military campaign. The Houthis will not stop fighting until they fully control Marib, Hodeidah, and Taiz – at a minimum.

The Houthis’ international positioning

Iran and Hezbollah

The Houthis have very few international allies. They are generally distrustful of the mechanisms and bodies of international diplomacy and the international community, which they view as being controlled by their enemies, primarily Saudi Arabia, the US, and Israel.

The Houthis’ key relationship is that with Iran, which has expanded and deepened over the course of the conflict. The Houthis are Iran’s cheapest ally in the region, enabling Tehran to cause serious problems for its main regional rival, Riyadh, at very low cost. The Iranian-Houthi relationship is grounded in shared interests and goals rather than ideological belief. Iran’s main goal in Yemen is the same as it is regionally – to confront and weaken both Saudi Arabia and the US politically, economically, and militarily. Initially, one key driver of Iranian involvement in Yemen was to divert Saudi attention and resources away from the Syrian conflict. For Iran, sustaining its long-running alliance with the Assad family was far more strategically important than gaining a foothold in Yemen. Since then, Iran’s investment in Yemen has grown. More recently, Iran has been subjected to a US maximum pressure campaign, and has deepened its engagement in Yemen in response to Saudi Arabia’s backing for the Trump administration. Iran has sought opportunities in Yemen to impose a cost on Saudi Arabia for its continued cheerleading of the US withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal and the US imposition of crippling sanctions against it. The Houthis publicly took credit for the September 2019 missile attack on Saudi Aramco’s main domestic oil processing facilities – a direct response to the US – although it was almost certainly carried out by Iran or an Iranian proxy in Iraq. In this case, the Houthis signalled support for Iran as part of their ‘swaggering’ strategy of displaying military prowess at little cost (as they have with occasional parades supporting Iranian leaders and Hezbollah).

The Houthis will continue to participate in Iran’s scheme to weaken Saudi Arabia so long as this strengthens their rule in Yemen. Rather than being proxies of Iran (as they are often described), the Houthis are equal partners in a shared military project that benefits both parties. But the Houthis are, above all, Yemeni actors pursuing domestic goals. They would continue the war even without Iranian support. It is a mistake to assume that Iran can direct Houthi behaviour.

While the Houthis inherited much of their expertise, technology, and weapons from Yemen’s security apparatus in 2014 when they seized the government, their ability to develop their tactical skills on the battlefield has come through technical assistance from Iran. Prior to the war, the Houthis were capable of building armoured vehicles and weapons from salvaged scrap. Currently, they have the ability to produce weaponry on a par with Iranian products thanks to Iranian transfers of knowledge and equipment, such as drones, missiles, and anti-tank weapons. The UN Panel of Experts has also linked some of the Houthis’ technology to financing from Iranian nationals.

In addition to their direct ties to Iran, the Houthis have allies in the Lebanese, Iranian-allied Hezbollah, which also provides battle strategy guidance. Lebanon, which was never a part of the Saudi-led coalition, provides the Houthis with a space to improve their skills, and is one of the few Arab countries that will broadcast Houthi media. Sources close to the Houthis confirm that small expert teams from Hezbollah are on the ground in Yemen, and have taught the Houthis how to make missiles efficiently. But, unlike Shia armed groups in Iraq and Lebanon, the Houthis are not trans-Shia actors intent on accumulating power outside Yemen. This is mainly because they do not see themselves as agents of Shi’ism fighting a larger regional war against Sunnism. While their rhetoric may be Shia jihadist, anti-American, and anti-Zionist, the Houthis are fundamentally indigenous Yemeni actors with indigenous Yemeni concerns. Even if Iran were to completely cut off aid to the Houthis, the group is self-sufficient and capable enough to threaten Saudi Arabia on its own, as demonstrated by its historical success against the Saudi-led coalition prior to strengthening its relationship with Iran.

The International community: Mediators, the United Nations, and Saudi Arabia

As the only GCC state that has remained outside the anti-Houthi coalition, Oman has the potential to act as a mediator in the Yemen conflict. The Houthis are dependent on Oman as the only Arab country able to provide them with a neutral space to communicate with the rest of the world. Throughout the war, Oman has served as a location for peace discussions; most recently, in 2019, when it hosted indirect talks between Houthi and Saudi officials. Oman has facilitated deals to limit certain types of localised violence and been a key site for the Houthis’ meetings with European and US actors.

Oman’s relationship with the Houthis and position in the Yemen conflict is an extension of its commitment to regional neutrality; Oman has maintained the respect of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates while providing the Houthis with a neutral space to communicate with the rest of the world.

The Houthis are active and keen participants in the UN peace process, regardless of its lack of success to date. It provides them with an international platform and a forum in which they can address the IRG. UN recognition of the Houthis as a partner in the negotiations gives them the legitimacy that the IRG denies them. The United Nations, therefore, provides the group with an opportunity to not only issue their demands to the world at large but also put pressure on their main opponents, the Saudi-led coalition, as well as on the IRG.

The longest and most serious negotiations between the Houthis and their enemies took place in Kuwait in 2016 under UN auspices. This was the third meeting between the Houthis and the IRG, in which they came close to reaching an agreement. Its failure led to the abandonment of any formal discussions until December 2018, following the UN-sponsored Geneva meeting between the Houthis and the IRG earlier that year (which failed because the UN was unable to guarantee safe travel for the Houthi delegation). In December 2018, the warring parties concluded the Stockholm Agreement, which helped secure a fragile ceasefire in Hodeidah. This came about following considerable international pressure, particularly by the US on Saudi Arabia. At the time, Riyadh was in a weak position internationally following the assassination of journalist Jamal Khashoggi in October 2018.

As of October 2020, the UN is focused on trying to persuade the Houthis and the IRG to agree on a joint declaration, which comprises a series of measures including a nationwide ceasefire, the release of prisoners, and the World Health Organization’s support for a joint IRG-Houthi unit to deal with covid-19. The UN also seeks to persuade the parties to resume talks based on the “three references”: UN Security Council Resolution 2216, the outcomes of the NDC, and the 2011 GCC Agreement – the very references that the Houthis have rejected since 2015, and that form the basis for the legitimacy of the Hadi government.

On the Houthi side, this UN political track is hamstrung by two key issues. Firstly, the ascendant hardline faction within the Houthis continues to see military advances as the key to securing their position, as reflected in the offensive on Marib. Secondly, Houthis of all hues consider Saudi Arabia to be their main enemy – especially since the UAE’s partial withdrawal of its military forces from Yemen in 2019 – and, therefore, their main interlocutor in achieving a settlement. The Houthis consider Hadi’s IRG – with which it engages in negotiations at the UN – to be largely secondary.

Here, Houthi positioning is increasingly driven by Saudi determination to seek an exit from the Yemen quagmire. This has opened up talks between the two sides, which became public in autumn 2019. However, Houthi military gains on the ground and the new Saudi position have emboldened the ‘extremist’ military wing of the Houthi movement, which hopes to benefit from Riyadh’s determination to end the conflict.

The main indication of the group’s current position on both Riyadh and the IRG is found in a document released in April 2020, when Saudi Arabia proposed a ceasefire. Resembling a wish list, it includes all the issues of concern to the Houthis and allocates full responsibility for fulfilling them to the Saudis, while the group only commits itself to a cessation of hostilities and an end to attacks on Saudi Arabia. This ambitious, maximalist set of demands entirely excludes the Hadi government by name, and leaves intra-Yemeni negotiations as a brief appendix of issues to be addressed once the main conflict has ended.

The scope of these demands demonstrates the Houthis’ self-perception as victors who do not need to make concessions. Further demands include the opening of Sanaa airport, recognition of Houthi authority within the parts of the country they control, and an end to the blockade begun by Saudi Arabia in 2015. These demands are not unreasonable and fit with UN efforts to achieve a solution to the conflict. On top of this, however, the group is demanding significant reparations and financial contributions to salaries. The Houthis are unlikely to abandon these demands any time soon.

To be sure, Yemen’s future relationship with Saudi Arabia is also an issue of considerable debate within the Houthi movement. Some Houthi leaders are concerned with regaining access to Saudi financial assistance, while others view the country as an eternal enemy due to its de facto alliance with Israel, its close relationship with the US, and its role in the destruction caused by the war. But, ultimately, the Houthis believe that their war will be won on the battlefield rather than at the negotiating table. The refusal of the IRG and their Saudi backers to recognise the Houthis as a parallel state actor inhibits their willingness to engage at the international level. With no regional or international backer that can be credible vis-à-vis the US and others, the Houthis can extract political concessions only through their military victories. For these reasons, the Houthis continue to feel extremely isolated and increasingly desperate to receive recognition as a formal state actor.

What Europeans should do

The European Council’s meeting in February 2019 reaffirmed its commitment to Yemen as a unified state, and its support for the UN-led political process. Several EU member states have been active in seeking solutions to the Yemeni conflict. France and Germany are among those with full-time Yemen embassies, though none are based in the country. Sweden is particularly engaged with the political track, trying to build on the Stockholm Agreement. As of September 2020, the EU and its member states, led by Germany and Sweden, had contributed a total of $342,884,000 to the UN’s annual humanitarian appeal, or 22 per cent of all funding.

But Europeans can play a greater role in advancing their interests in Yemen and supporting efforts to end the conflict and stabilise the country. They could start by achieving greater EU agency in international efforts. The exclusion of the EU and its member states from the international ‘quartet’ – made up of the US, the UK, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE – has long reduced European influence. While this group has been dormant in recent months, the EU should push for its revival. Sweden and Germany could lead a meeting on the margins of the 2020 UN General Assembly that involved all the main conflict actors, except the Houthis. This could form the basis of a wider grouping that included the EU and provided space for its leading member states, thereby adding weight to efforts to find a solution. Having done so, Europeans should then step up their efforts in the following ways.

Expand conditional engagement with the Houthis

The Houthis’ military gains in 2020 indicate that their political influence and military forces are unlikely to weaken any time soon. The likelihood is that they will retain long-term control of the Zaydi parts of the country, as well as many of the surrounding Shafi areas currently under their control. This means that around 20 million Yemenis will continue to live under Houthi rule. Europeans need to accept that progress in ending Yemen’s political and humanitarian catastrophe will necessitate widened engagement with the Houthis. While the Houthis’ current position does not easily lend itself to a constructive turn of events, Europeans should recognise that ongoing conflict, polarisation, and isolation will only further empower hardline forces.

Europeans should now aim to press for openings that facilitate an incremental shift in internal dynamics towards a more constructive path. They should use channels of communication with the Houthis, and the incentive of wider international recognition, to press them to better respect human rights and demonstrate greater administrative inclusion in areas under their control. Europeans need to focus support on providing space for civil society and other political and ideological groups. They should also concentrate their efforts on the education system, given that the Houthis’ indoctrination of generations of Yemenis is one of the most troubling aspects of their rule, with dangerous long-term implications for security and human development in Yemen. Europeans should make clear to the Houthis that the degree of international legitimacy, and any subsequent international assistance to the country, is dependent on the group making progress on these fronts. Given Yemen’s desperate humanitarian and economic situation, the Houthis may face increased internal pressure and turn to external supporters, with accompanying opportunities for European governments to press for positive shifts in these areas.

To better operationalise this track, the EU must maintain and expand its direct ties with Sanaa. European states have had limited engagement with the Houthis in recent years, with officials engaged in occasional talks inside Yemen. The most recent such visit was in January 2020, after Saudi Arabia gave permission for the delegation to access Yemeni airspace. This channel needs to be expanded. Building on current engagement, the European External Action Service should increase dialogue and exchanges with Houthi leaders. It should encourage member states to do the same, so long as they coordinate their policy positions, including with the UN, with the aim of securing a ceasefire, opening up humanitarian space, and advancing a much-needed inclusive political process. This can be done by allowing European officials to fly more regularly into Sanaa – a step that would require European pressure on Riyadh to allow such flights, as well as to permit Houthi representatives to travel to Oman and other neutral nations for negotiations. The EU and its member states should recognise further involvement of the Houthis in track II and other indirect initiatives as a way to help them develop more constructive approaches toward the political track.

Meanwhile, European states should oppose any decisions by other external powers to designate the Houthis as a terrorist group, a step the EU should not follow. This is a risk if Donald Trump secures a second term as US president and seeks to ratchet up the maximum pressure campaign against Iran – particularly given Saudi pressure to sanction the group. Putting the Houthis on the terrorism list will further inhibit the most populous and the most suffering regions in Yemen from accessing humanitarian aid.

Encourage Houthi-Saudi and intra-Yemeni negotiations

Europeans should double down on their support for negotiations between Saudi Arabia and the Houthis. Over the past year, the UK has already assumed an increasingly important role in doing so to halt Saudi airstrikes and Houthi drone attacks.[2]Ultimately, the disarray prevailing within the anti-Houthi front may encourage Saudi Arabia to want a deal that would secure its border and end missile strikes and other military incursions in its territory. (The UAE’s military retreat from the war, the financial burdens of covid-19, and low oil prices, as well as the extremely high cost of the Yemen war, increasingly strain Saudi finances.) In return, the Houthis could be incentivised to see the gains they would make from securing an agreement that initially acknowledges their control over the north and provides them with international recognition, as part of a package that aims to support a wider, UN-led political process. Although some Houthis favour ongoing conflict, international actors should make greater efforts to persuade all parties to see this as the necessary and best outcome still available, including by laying out the prospects for more international support to the country if a ceasefire and political process makes progress. Here, the possibility of a new US administration under Joe Biden could provide an opening for a joint US-European push, given the widespread desire among US Democrats to end the war and re-energise diplomatic pathways out of conflicts in the Middle East. The devastation resulting from the Marib offensive should lend urgency to these efforts.

While their focus may initially be on Houthi-Saudi talks, Europeans should make an explicit link with the need to subsequently restart the UN process. As part of this, they should press the Houthis to engage in intra-Yemeni talks – again, despite the Houthis’ current indifference to this track. The Houthis’ geographical focus on the north suggests there may be space for negotiations with the south as part of a broader agreement. Here, European governments should try to work with the UAE in bringing the different parties together, given the country’s longstanding relationship with the Southern Transitional Council.

As part of the commitment to reaching a political solution in Yemen, European countries should also halt weapons flows to all belligerents in the war. As major arms sellers, France and the UK will be critical to such efforts. EU countries can also step up coordination with the UN to increase the interdiction of arms flows to Yemen from regional actors, most notably Iran.

Talk to Iran about Yemen

The EU, Germany, France, and the UK differ from the US in that they have tried to continue productive dialogue with Iran in recent years, aiming primarily at salvaging the nuclear agreement, but also focusing on regional security. On the latter, their talks have concentrated on Yemen. Here, Iran has sometimes constructively engaged with the issue, both on the sidelines of the Stockholm negotiations and by arranging talks between the Houthis and European diplomats in summer 2019.

European states should maintain this dialogue to try to create positive movement from the Houthis, albeit without overstating the influence that Tehran can bring to bear in ending the conflict nor downplaying the need for direct engagement with the Houthis. Iran does not dictate policy on the Houthis, but they have a close relationship that Europe can actively utilise through its engagement with Tehran. This track will clearly have more chance of success if a Biden administration takes power in the US, allowing for a possible resumption of the nuclear agreement, a turn to regional diplomacy, and abandonment of the maximum pressure campaign on Iran. If there is to be any progress in the region, Yemen would clearly be the most likely and promising venue given that Iran has fewer strategic interests in the conflict relative to other parts of the region.

Increase humanitarian aid

It is clear that addressing the key issues affecting Yemenis’ daily lives will necessitate an increase in humanitarian assistance. The first move towards meeting Yemen’s overwhelming humanitarian needs should be ending the Saudi-led maritime, land, and air blockade on the country. While international actors, particularly Saudi Arabia, might be reluctant to give in to such a fundamental Houthi demand without extracting concessions from the group, the end of the blockade must be depoliticised to the extent that it is seen as, fundamentally, a humanitarian act. This will ease the plight of millions suffering from siege-related food, fuel, and medicine shortages.

Here, Europeans must simultaneously address the issue of Houthi interference in flows of humanitarian assistance, particularly those of medical supplies during the covid-19 emergency. Europeans will need to make clear that, without greater transparency on the ground, international aid will not flow into the country, likely increasing internal pressures on the Houthis. This will require intense and detailed direct negotiations with the Houthi movement to secure the necessary guarantees and monitoring mechanisms, but will undoubtedly mean compromising with them on other issues.

More broadly, boosting the UN’s aid resources for Yemen is essential, given the fact that less than 40 per cent of the UN’s humanitarian appeal has been funded as of 1 October. Total pledges made at the June conference were only 54 per cent of the amount required, a figure that was largely estimated without accounting for covid-19 needs in in Yemen. As the countries directly involved in the conflict (principally, Saudi Arabia and the UAE) are among the richest in the world, they should increase funding support for Yemen. But Europeans cannot shy away from this responsibility either.

Conclusion

Six years into the internationalisation of Yemen’s civil war, Europeans’ diplomatic involvement in the crisis is still formally based on the situation prevailing in 2015. UN Security Council Resolution 2216, adopted in April 2015, is long out of date – as demonstrated by the Houthis’ increasing power in Yemen. The Houthis now play a dominant role in the country and, despite some internal political differences, they remain a close-knit, effective force. The group is unlikely to soften its approach or reveal internal differences so long as the fighting continues.

The Houthis, with all their terrible characteristics, are an inescapable part of the political landscape in Yemen and will be an unavoidable partner in securing desperately needed progress in the country. The international community’s priority must therefore be to broaden its engagement with the Houthis, engaging regional actors as it does so – with the ultimate aim of bringing Yemeni actors to the negotiating table, while pressing for improved conditions for the populace at large.

About the authors

Helen Lackner is a visiting fellow at the European Council for Foreign Relations and research associate at SOAS University of London. Her most recent book is Yemen in Crisis: Autocracy, Neo-Liberalism and the Disintegration of a State (published by Saqi Books in 2017; by Verso in 2019; and in Arabic in 2020). She is the editor of the Journal of the British-Yemeni Society and a regular contributor to Open Democracy, Arab Digest, and Oxford Analytica. For ECFR, she has previously written “War and pieces: Political divides in southern Yemen”, with Raiman al-Hamdani. She also speaks on the Yemen crisis at many public events, and has done so in the British House of Commons.

Raiman Al-Hamdani is a visiting fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations and a researcher at the Yemen Policy Center and ARK Group. His academic and professional work focuses on issues of security and development in the Middle East and North Africa. Al-Hamdani has been active in the field of development, volunteering at schools for disabled children, working in camps for internally displaced persons, and representing Yemen at the UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations. He holds a master’s degree in international security from the American University in Cairo, and a master’s in development from SOAS University of London. For ECFR he has previously written “War and pieces: Political divides in southern Yemen”, with Helen Lackner.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank all those who have contributed to our work through shared information, comments, and suggestions. As most of them – be they in Yemen or elsewhere – have chosen to remain anonymous, no names are listed. The authors remain responsible for the views and any remaining errors in the text. They particularly appreciate the important and helpful input of ECFR’s Julien Barnes-Dacey, Ellie Geranmayeh, and Adam Harrison, all of whom helped improve the text and analysis.

[1] Based on author conversations and interactions with locals who support the Houthis.

[2] Interviews with official sources speaking under the condition of anonymity.

Charts on “Houthi command and control structure” and “The Houthis’ parallel governing structures”: “Yemen: The Houthi Supervisory System”, ACAPS, 17 June 2020.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.